At the start of the ’80s, Queen looked invincible. Their popularity had not only survived the punk storm but grown exponentially.

When punk first hit, Paul Rodgers, the man who’s been chosen to front Queen in 2005, was singing with Bad Company, who’d enjoyed worldwide hits with “Can’t Get Enough” and “Feel Like Makin’ Love”.

“When the Pistols and The Clash came along, bands like Bad Company became dinosaurs overnight,” Rodgers tells Uncut. “Suddenly, nobody wanted to know us. Whereas Queen just got bigger and bigger. They seemed to ride over punk, regardless. Just as they rode over other musical fashions. They were just so well-defined. They were a law unto themselves. Nothing could touch them.”

“Another One Bites The Dust” confirmed their status as America’s favourite band, selling 4.5 million copies. In the UK, “Under Pressure” (featuring David Bowie) was their best-seller to date, and their 1981 Greatest Hits entered at No 1, staying in the charts for 312 weeks. They also cracked South America, their 1981 tour culminating in a gig at São Paulo’s Morumbi Stadium for 131,000 fans.

But with the new decade, tastes were changing, and there were signs of Queen losing momentum. Yes, they’d ridden out punk. But whether they could survive in the post-punk era of new romanticism, white funk and the new electronic pop being made by Sheffield bands like ABC and The Human League was another matter.

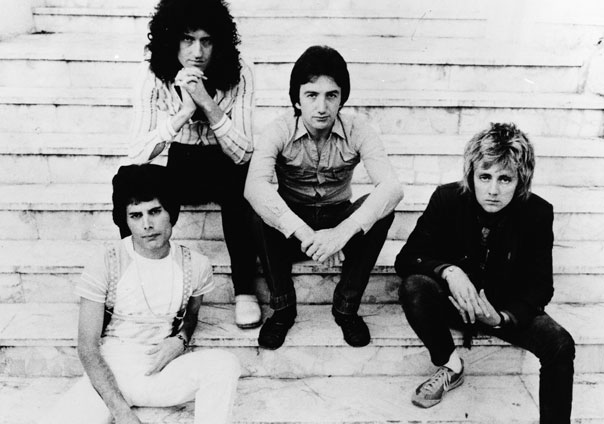

Their 1980 Flash Gordon soundtrack and 1982’s ill-conceived, dancefloor-oriented Hot Space were conspicuous flops. American sales dipped alarmingly once Mercury dropped his trademark ‘flash and glitter’ image and adopted a gay clone look of short-cropped hair, ‘flavour-savour’ moustache, PVC trousers and leather-and-chain cap. And, behind the scenes, Queen’s unrelenting regime was taking its toll. There was growing in-fighting, including a mass backstage brawl at a 1984 Italian festival, as the group’s vastly contrasting personalities began to clash under the phenomenal weight of their success. In contrast to Mercury’s flamboyance, Brian May fretted and fussed and suffered from long bouts of manic depression. Meanwhile, Roger Taylor seemed hell-bent on out-grossing Freddie in the rock slut stakes, while John Deacon played the stoical bass player to perfection, just as John Paul Jones did in Led Zeppelin. The psychological complexities of the relationship between the four of them would have required an army of analysts to resolve, and at times threatened to tear them apart.

Both Taylor and May embarked on solo projects, while Mercury occupied himself with a series of extra-curricular ventures, including a songwriting stint with Michael Jackson (abruptly terminated when Jackson wandered into the studio lounge to find Mercury snorting coke through a $100 bill).

As May explains, it was make-or-break time for Queen. “The excess leaked out from the music into life and became a need,” he says. “As a band, we were always trying to get to a place that had never been reached before and excess is a part of that. It was all like a fantasy to see how far we could go. And that started to take its toll. We were all out of control. We’d gone to a place that was difficult to recover from.”

Recover they did, storming back in 1984 with “Radio Gaga” and “I Want To Break Free”. Yet it was hard to shake the suspicion that Queen had reached the summit of their potential.

Then came their thoughtless eight-show visit to Sun City in South Africa in the autumn of ’84. Apartheid was at the height of its obnoxious design, and Sun City was the regime’s most notorious whites-only entertainment complex in the so-called ‘homeland’ of Bophuthatswana. The British Musicians’ Union had imposed a boycott on South Africa as far back as 1961. The Beatles and the Stones had refused to play there, and most bands with any social conscience or even with a less altruistic concern for their own reputation had likewise declined to play to South Africa’s racially segregated audiences. Queen waded straight in, earning a place on the UN’s cultural blacklist as a result, as well as the opprobrium of rock’s right-on community, which had never liked their brashness anyway.

The backlash eventually forced them to promise never to go back, and May and Taylor’s support today for Nelson Mandela’s anti-Aids charity 46664 (named after his Robben Island prison number) can be seen as part of an ongoing determination to make amends. That they managed to ride the Sun City storm was probably down to a single, fateful phone call from Bob Geldof.