Among my post last week, I received a nice care package from Ace Records that included one quite weird Duke Ellington album ("My People"); Volume 3 of their "Where Country Meets Soul" series (I cannot recommend Ralph ''Soul'' Jackson's version of ''Jambalaya'' highly enough); and, maybe best of all, "Cracking The Cosimo Code", a collection of extraordinary music originating from Cosimo Matassa's New Orleans studio in the 1960s. A couple of days later, by unhappy coincidence, the news came through that Matassa, discreet architect of much of what we now know as the New Orleans sound (and perhaps even rock'n'roll itself) had died at the age of 88. I must admit, Matassa was one of those people I hadn't realised was still alive. In May, when I was in New Orleans to write about Hurray For The Riff Raff, I would wake up early and go wandering out of my hotel and into the French Quarter. One morning, I came across the unassuming corner store pictured above, the family deli where Matassa worked after he retired from the music business in the 1980s. I don't think this is the original site of the Matassa Market where the young Cosimo set up his first studio in the 1940s, hooking up with Fats Domino for a series of R&B records that would act as prototypes for the next great leap forward in musical evolution. In his sleevenotes for "Cracking The Cosimo Code", John Broven quotes Matassa telling how Domino "was a pain in the ass to record. Not because he was a nasty guy or anything, but right in the middle of a take he'd say, 'How do I sound?' Pretty bad, especially if it's the first good take of the thing you had." http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aIz1cPfTRW4 By the '60s, and the period covered by "Cracking The Cosimo Code", Matassa's operation had moved to a fractionally less homespun location on Governor Nicholls Street, which became the crucible of New Orleans music over the decade. Matassa engineered many of the sessions, while a list in the CD sleevenotes, titled "Musicians On These Recordings Include…", is testament to the wealth of talent focused in this tiny hub. The piano players listed, for example, runs "Allen Toussaint, Harold Battiste, Mac Rebennack, Willie Tee. Tee's own "Teasin' You" (written by another key player here, Earl King) is one of the key tracks on the fantastic compilation; sprightly rhythm, the subtlest of horn stabs and thin guitar lines; a vocal that's soulful but not histrionic, imbued with the easygoing pleasure that crackles through so many of Matassa's productions. Like so much music that emerged from Southern studios in the 1960s - Muscle Shoals and Stax being obvious examples - these are sessions that radiate a sense of efficiency and good times running in unusual harmony. You can only imagine that those vibes were facilitated in no small part by Matassa himself: Broven writes, of his first meeting with Matassa in 1973, that he was "struck by his friendly persona and gentle self-deprecating humour, allied to the sharpest of minds." As "Cracking The Cosimo Code" proves, that friendly persona midwifed a bunch of deathlessly magnificent R&B records: you'll find here "Trick Bag" by the aforementioned Earl King, Lee Dorsey's "Get Out Of My Life, Woman", Aaron Neville's "Tell It Like It Is", Robert Parker's "Barefootin'", "The Monkey Speaks His Mind" by another of Matassa's critical collaborators, Dave Bartholomew. Like the best compilations of this kind, though, it's some of the lesser-known cuts (to a dilettante like me, at least) that are revelatory. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m5tzzi2rCLQ Oliver Morgan's "Who Shot The Lala" is sinewy, call and response proto-funk from 1963 (probably produced by Eddie Bo, the sleevenotes speculate; the Matassa catalogue is speckled with such grey areas) that captures that quintessential New Orleans paradox of creating celebratory music out of tragedy; in this case the death of another musician, Lawrence "Prince La La" Nelson (Wikipedia, incidentally, records Nelson's death as due to a drug OD, rather than a shooting). http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hpxGTZz7A38 Danny White's 1962 version of "Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye", meanwhile, is a heavily blues-infused southern soul burner, with White's eloquent yearning doubled by the stinging micro-guitar solos that sit between his entreaties. It's a great record, and a fitting showcase to the work of a musical technician who gave his charges the space and the confidence to express themselves so wholeheartedly. If you want to read a much more thorough and authoritative obituary of the remarkable Matassa, by the way, I should direct you to this great piece on www.nola.com. Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey

Among my post last week, I received a nice care package from Ace Records that included one quite weird Duke Ellington album (“My People”); Volume 3 of their “Where Country Meets Soul” series (I cannot recommend Ralph ”Soul” Jackson’s version of ”Jambalaya” highly enough); and, maybe best of all, “Cracking The Cosimo Code”, a collection of extraordinary music originating from Cosimo Matassa’s New Orleans studio in the 1960s.

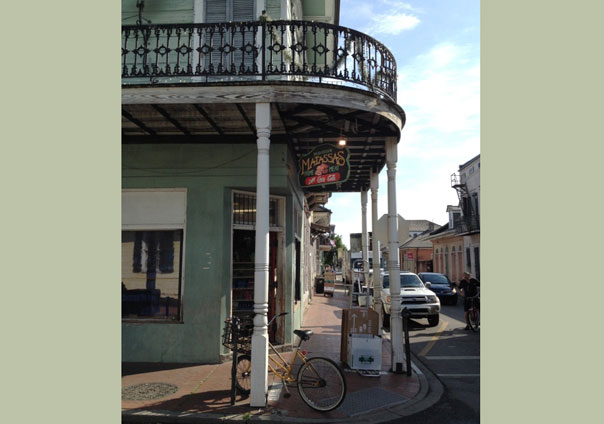

A couple of days later, by unhappy coincidence, the news came through that Matassa, discreet architect of much of what we now know as the New Orleans sound (and perhaps even rock’n’roll itself) had died at the age of 88. I must admit, Matassa was one of those people I hadn’t realised was still alive. In May, when I was in New Orleans to write about Hurray For The Riff Raff, I would wake up early and go wandering out of my hotel and into the French Quarter. One morning, I came across the unassuming corner store pictured above, the family deli where Matassa worked after he retired from the music business in the 1980s.

I don’t think this is the original site of the Matassa Market where the young Cosimo set up his first studio in the 1940s, hooking up with Fats Domino for a series of R&B records that would act as prototypes for the next great leap forward in musical evolution. In his sleevenotes for “Cracking The Cosimo Code”, John Broven quotes Matassa telling how Domino “was a pain in the ass to record. Not because he was a nasty guy or anything, but right in the middle of a take he’d say, ‘How do I sound?’ Pretty bad, especially if it’s the first good take of the thing you had.”

By the ’60s, and the period covered by “Cracking The Cosimo Code”, Matassa’s operation had moved to a fractionally less homespun location on Governor Nicholls Street, which became the crucible of New Orleans music over the decade. Matassa engineered many of the sessions, while a list in the CD sleevenotes, titled “Musicians On These Recordings Include…”, is testament to the wealth of talent focused in this tiny hub. The piano players listed, for example, runs “Allen Toussaint, Harold Battiste, Mac Rebennack, Willie Tee.

Tee’s own “Teasin’ You” (written by another key player here, Earl King) is one of the key tracks on the fantastic compilation; sprightly rhythm, the subtlest of horn stabs and thin guitar lines; a vocal that’s soulful but not histrionic, imbued with the easygoing pleasure that crackles through so many of Matassa’s productions. Like so much music that emerged from Southern studios in the 1960s – Muscle Shoals and Stax being obvious examples – these are sessions that radiate a sense of efficiency and good times running in unusual harmony. You can only imagine that those vibes were facilitated in no small part by Matassa himself: Broven writes, of his first meeting with Matassa in 1973, that he was “struck by his friendly persona and gentle self-deprecating humour, allied to the sharpest of minds.”

As “Cracking The Cosimo Code” proves, that friendly persona midwifed a bunch of deathlessly magnificent R&B records: you’ll find here “Trick Bag” by the aforementioned Earl King, Lee Dorsey’s “Get Out Of My Life, Woman”, Aaron Neville’s “Tell It Like It Is”, Robert Parker’s “Barefootin'”, “The Monkey Speaks His Mind” by another of Matassa’s critical collaborators, Dave Bartholomew. Like the best compilations of this kind, though, it’s some of the lesser-known cuts (to a dilettante like me, at least) that are revelatory.

Oliver Morgan’s “Who Shot The Lala” is sinewy, call and response proto-funk from 1963 (probably produced by Eddie Bo, the sleevenotes speculate; the Matassa catalogue is speckled with such grey areas) that captures that quintessential New Orleans paradox of creating celebratory music out of tragedy; in this case the death of another musician, Lawrence “Prince La La” Nelson (Wikipedia, incidentally, records Nelson’s death as due to a drug OD, rather than a shooting).

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hpxGTZz7A38

Danny White’s 1962 version of “Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye”, meanwhile, is a heavily blues-infused southern soul burner, with White’s eloquent yearning doubled by the stinging micro-guitar solos that sit between his entreaties. It’s a great record, and a fitting showcase to the work of a musical technician who gave his charges the space and the confidence to express themselves so wholeheartedly. If you want to read a much more thorough and authoritative obituary of the remarkable Matassa, by the way, I should direct you to this great piece on www.nola.com.

Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey