Another night at the opera, with demos and live versions... Another year, another ‘remaster’. Techies may claim otherwise, but one suspects the best way to listen to The Who's ‘rock opera’ is still via the primal technology of unscratched vinyl and a decent valve amplifier. For those hungering to hear Pete Townshend’s tale of the deaf, dumb and blind kid turned guru in 5:1 surround sound, however, here’s the ‘super deluxe’ version at an eye-watering £80, which also buys you 20 unreleased demos from Pete’s vaults, a 1969 concert performance (dubbed ‘bootleg’ though garnered from an official recording), a 20,000 word book by chronicler Richard Barnes and a repro poster. The deluxe edition delivers just the original and concert versions at a more manageable £14. The sonics of Tommy have always been a singular case in The Who’s catalogue, eschewing the bright pop sound of their early work without embracing the heavy rock dynamics that were already the norm on stage and which followed on Who’s Next. Instead came what Townshend called “deliberate blandness”, with Roger Daltrey’s vocals foregrounded over Townshends’s layered acoustic guitars, a modest input of power chords and Keith Moon’s hyper-active drumming set back in a production Moon found “very un-Who like”. Richard Barnes’ account of the album’s creation reveals that manager/producer Kit Lambert, in a hurry to get to Egypt, left the mix to engineer Damon Lyon-Shaw, albeit with detailed instructions. The band’s fear was that Lambert was planning orchestral overdubs; instead, he simply wanted Tommy to sound uncluttered. The concert version (mostly from a single Canadian show late in 1969) prove Lambert’s ideas were right. The performances have their moments – Daltrey is mostly outstanding – but Tommy live is a very different animal, with Townshend’s guitar, often turned up to eleven, weighing heavily on the songs’ drama. No shortage of power chords here – check the noisy “Amazing Journey” – or of Moon’s kit-thrashing. There’s no “Underture” and the piece emerges, inevitably, more rock than opera. The demos are another matter. Firstly they show just how meticulously the 20 year old Townshend planned Tommy, at least musically. There are few surprises compared to the finished album; Pete’s reedy pipes replace Roger’s gutsy holler, but the musical parts are all in place, though often played on shonky piano rather than guitar. Lyon-Shaw describes recording proceeding with a minimum of fuss. “The band would listen in the control room, talk over what was required, and then go to into the studio and re-interpret the demos. It was usually quite spontaneous. Very few bands could grasp what was played on demos and re-interpret the ideas into a finished product." The demos’ notable departures include a substantial amount of reverse guitar on “Amazing Journey” – the genesis of the entire opera according to Townshend – and on something called “Dream One”, an instrumental psych ramble studded with feedback and whoopee whistle. Ah, the joys of a home studio. Also included among the demos is a band version of Mose Allison’s “Young Man Blues”, a song that clearly wouldn’t leave Townshend alone, and which he hoped to include on Tommy alongside Allison’s “Eyesight to the Blind” (which became “The Hawker”). At under three minutes it’s a more concise and appealing take of the number than the pumped-up version on Live At Leeds, though still with Townshend’s guitar at its gnarliest. A find. The mini-book by Barnes, a friend from Townshend’s art school days, proves exhaustive and occasionally exhausting. It’s richly illustrated, prominent among the exhibits being the notebooks and envelopes on which Townshend planned ideas and jotted songs (a gloriously tatty “Pinball Wizard” among them). Tommy’s evolution from vibes-tuned autistic kid to pinball-playing guru was circuitous, receiving a vital shove from writer Nic Cohn, who judged what he heard “po-faced” and suggested the pinball motif. The ideas of Townshend’s adopted guru, Meher Baba, were always central, though fellow follower Mike McInnerney, who designed the artwork, rejects any idea of proselytising. “We’re not the Mormons!” he snorts. The opera’s plot, which bassist John Entwhistle claimed he “never understood before I saw the film”, remains unconvincing, but the spine of great songs on which Tommy is built – “Acid Queen”, “Sensation”, “I’m Free”, “Amazing Journey” among them – along with the catchy bridges and bravura playing, overcome its problems. “People who couldn’t get into the spiritual end of it could see it as a huge cartoon strip,” judged Townshend. Tired of playing crowd pleaser “Magic Bus” (“a nonsense number”), his opus renewed him. “With Tommy in our back pocket I felt I was riding two horses at once: a clod-hopping pantomime version on one hand, and a winged unicorn leading the heavenly host on the other.” Pete’s unicorn flew true. Tommy remains magnificent, the best (pace Arthur, Quadrophenia, Ziggy) of rock’s erratic operatic turns. Neil Spencer

Another night at the opera, with demos and live versions…

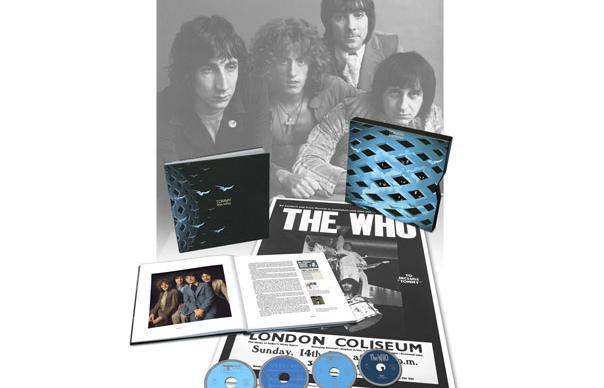

Another year, another ‘remaster’. Techies may claim otherwise, but one suspects the best way to listen to The Who‘s ‘rock opera’ is still via the primal technology of unscratched vinyl and a decent valve amplifier. For those hungering to hear Pete Townshend’s tale of the deaf, dumb and blind kid turned guru in 5:1 surround sound, however, here’s the ‘super deluxe’ version at an eye-watering £80, which also buys you 20 unreleased demos from Pete’s vaults, a 1969 concert performance (dubbed ‘bootleg’ though garnered from an official recording), a 20,000 word book by chronicler Richard Barnes and a repro poster. The deluxe edition delivers just the original and concert versions at a more manageable £14.

The sonics of Tommy have always been a singular case in The Who’s catalogue, eschewing the bright pop sound of their early work without embracing the heavy rock dynamics that were already the norm on stage and which followed on Who’s Next. Instead came what Townshend called “deliberate blandness”, with Roger Daltrey’s vocals foregrounded over Townshends’s layered acoustic guitars, a modest input of power chords and Keith Moon’s hyper-active drumming set back in a production Moon found “very un-Who like”.

Richard Barnes’ account of the album’s creation reveals that manager/producer Kit Lambert, in a hurry to get to Egypt, left the mix to engineer Damon Lyon-Shaw, albeit with detailed instructions. The band’s fear was that Lambert was planning orchestral overdubs; instead, he simply wanted Tommy to sound uncluttered.

The concert version (mostly from a single Canadian show late in 1969) prove Lambert’s ideas were right. The performances have their moments – Daltrey is mostly outstanding – but Tommy live is a very different animal, with Townshend’s guitar, often turned up to eleven, weighing heavily on the songs’ drama. No shortage of power chords here – check the noisy “Amazing Journey” – or of Moon’s kit-thrashing. There’s no “Underture” and the piece emerges, inevitably, more rock than opera.

The demos are another matter. Firstly they show just how meticulously the 20 year old Townshend planned Tommy, at least musically. There are few surprises compared to the finished album; Pete’s reedy pipes replace Roger’s gutsy holler, but the musical parts are all in place, though often played on shonky piano rather than guitar. Lyon-Shaw describes recording proceeding with a minimum of fuss. “The band would listen in the control room, talk over what was required, and then go to into the studio and re-interpret the demos. It was usually quite spontaneous. Very few bands could grasp what was played on demos and re-interpret the ideas into a finished product.”

The demos’ notable departures include a substantial amount of reverse guitar on “Amazing Journey” – the genesis of the entire opera according to Townshend – and on something called “Dream One”, an instrumental psych ramble studded with feedback and whoopee whistle. Ah, the joys of a home studio.

Also included among the demos is a band version of Mose Allison’s “Young Man Blues”, a song that clearly wouldn’t leave Townshend alone, and which he hoped to include on Tommy alongside Allison’s “Eyesight to the Blind” (which became “The Hawker”). At under three minutes it’s a more concise and appealing take of the number than the pumped-up version on Live At Leeds, though still with Townshend’s guitar at its gnarliest. A find.

The mini-book by Barnes, a friend from Townshend’s art school days, proves exhaustive and occasionally exhausting. It’s richly illustrated, prominent among the exhibits being the notebooks and envelopes on which Townshend planned ideas and jotted songs (a gloriously tatty “Pinball Wizard” among them). Tommy’s evolution from vibes-tuned autistic kid to pinball-playing guru was circuitous, receiving a vital shove from writer Nic Cohn, who judged what he heard “po-faced” and suggested the pinball motif. The ideas of Townshend’s adopted guru, Meher Baba, were always central, though fellow follower Mike McInnerney, who designed the artwork, rejects any idea of proselytising. “We’re not the Mormons!” he snorts.

The opera’s plot, which bassist John Entwhistle claimed he “never understood before I saw the film”, remains unconvincing, but the spine of great songs on which Tommy is built – “Acid Queen”, “Sensation”, “I’m Free”, “Amazing Journey” among them – along with the catchy bridges and bravura playing, overcome its problems. “People who couldn’t get into the spiritual end of it could see it as a huge cartoon strip,” judged Townshend. Tired of playing crowd pleaser “Magic Bus” (“a nonsense number”), his opus renewed him. “With Tommy in our back pocket I felt I was riding two horses at once: a clod-hopping pantomime version on one hand, and a winged unicorn leading the heavenly host on the other.”

Pete’s unicorn flew true. Tommy remains magnificent, the best (pace Arthur, Quadrophenia, Ziggy) of rock’s erratic operatic turns.

Neil Spencer