John Lydon has never received his due as a film critic. To be fair, we only really know the great man’s opinions on a single movie, but almost all his key objections to it are on the money. Three decades on, even the film’s director has largely come round to his way of thinking: “All the advice [Lydon] gave us, we should have followed…”

Alex Cox, quite cheerfully, makes this declaration in a short but fascinating interview included among the extras on this new edition of his 1986 biopic, tracing the downward spiralling love affair between Sid Vicious, his American girlfriend Nancy Spungen and heroin.

When the film first appeared, Lydon was vociferous in his condemnation of factual inaccuracies and a failure to look beyond Sid’s bloodied cartoon yob public image. For audiences not so intimately involved with the story – i.e. everyone else – those faults are less glaring. Indeed, it’s Cox’s balance between personal passion and ironic distance that gives this movie its particular life. Cox drew boundless inspiration from punk, but as the UK scene was breaking, he was already far away, a Brit-abroad in LA, soaking up the west coast iteration of punk that soundtracked his debut, Repo Man (1984).

Above all, though, Lydon objected to Cox’s final scene, and the damage it does is more profound. In reality, released from jail on bail under suspicion for the killing of Nancy Spungen in their Chelsea Hotel room, Sid scored more smack and swiftly died. In Cox’s movie, Nancy, resplendent in bridal white, comes back to earth to pick Sid up in a heavenly New York taxicab that ferries them off toward some strung-out punk Nirvana, away from a world never meant for ones as beautiful as them.

The sequence is one of several semi-surreal moments injected amid an otherwise fairly straight, if energetically cartoonish, rendering of recent history by Cox, who, directing only his second feature, was exploding with ideas. 1986 was a year of flux for British cinema. On one the hand, the 1960s old guard – Nic Roeg, Ken Russell and Alan Clarke – all released new movies that year, as did a new generation of punk-inspired filmmakers including Derek Jarman and Julien Temple.

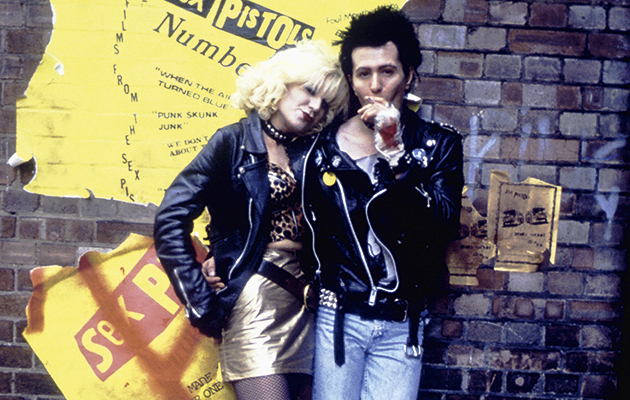

Cox fitted in well. It is the filmmaker’s anarchic poetic realism that makes Sid & Nancy linger in the mind, alongside two striking lead performances – in his movie debut, Gary Oldman brings to Sid both feral energy and a blockhead shtick reminiscent of Vyvyan from The Young Ones; as Nancy, Chloe Webb delivers a horrendous nasal whine that could cut concrete, yet suggests buried traces of a lost and damaged girl. Often, the film slips into dreamlike moments: a gorgeous long take of the couple walking unscathed amid the carnage as the Pistols’ Jubilee boat ride degenerates into a mini-riot; snogging in a Manhattan alley while garbage cans rain softly down around them.

Sid & Nancy is frequently funny, too. Miguel Sandoval’s scene as the American record company executive singing Johnny Rotten his “punky” song “I Wanna Job” is eternally hilarious. But the second half, as the couple fall into junkiedom, grows increasingly bleak and cold – until that last scene, a sentimentalised moment of rock death romanticism. Elsewhere, Courtney Love takes a small role as Nancy’s hanger-on friend.

But a curious, constant ambivalence is Sid & Nancy’s defining characteristic. Simultaneously seeking authenticity and subverting it, it is precisely this odd sense of pulling in different directions that makes all Cox’s films so fascinating – and also saw him quickly banished from the mainstream, following the commercial failure of his follow-up, Walker (1987).

If John Lydon has never forgiven Sid & Nancy, surely even he would appreciate that Cox made it with the best intentions. As he says here, the main reason he started it in the first place was to scupper another planned Sid & Nancy movie, projected, horrifically, to star Rupert Everett and Madonna. As for Lydon: “I have nothing but respect for the man, and I would love to see him again and embrace him warmly.” Maybe the BBC could get the two of them together to do a film review show.

EXTRAS 7/10: The Blu-Ray’s big draw is the new restoration, supervised by cinematographer Roger Deakins. Elsewhere, fine, if short, interviews with Cox, Deakins and Don Letts.