There’s a song on this, the second album by the veteran, late-flowering blues maverick Seasick Steve, called “Thunderbird”. Delivered in a gravel-voiced holler that recalls Tom Waits and a series of twisted southern vowels that resemble Dr John, the song is a hymn to the cheapo fortified wine of the same name, a drink that’s popular with both grizzled hobos and students alike. Rather fittingly, it appears to be students and grizzled hobos that comprise Seasick Steve’s core audience. Somehow, the sixtysomething guitarist and singer born Steve Wold has managed to resurrect and reinvent that long debased artform known as the blues, reclaiming it from the dreary boogie revivalists and finding a way of selling it to audiences brought up on The White Stripes. He’s done this primarily by reconnecting the blues to its earliest solo incarnations, the music of Robert Johnson and Charlie Patton. Part of the reason why those early kings of the delta sound so haunted and ethereal today is because – unhampered by drummers of bass players – they didn’t follow such rigid, 12-bar-blues templates. A cycle might last 12 bars but it might just as easily be 11, 13 or 14 or 22 bars long, and they’d often switch time signature at random. Rarely would they use the same three-chord turnarounds: sometimes they’d play in a single key, or use weird chromatic chord changes. Seasick Steve does all of this, and his one-man-band status also allows him to explore a more wayward tributary of the Mississippi – one in which Robert Johnson’s solo voyages merge with the avant garde soundscapes of Moondog, the minimalism of Steve Reich and the drone rock of the Velvet Underground. Like Moondog, Steve tries to recreate the sounds in his head by inventing his own mutant instruments (indeed, Steve’s three-stringed “piece of shit” Tranz Wonder guitar is not dissimilar from Moondog’s three-string Oo-yat-su). Like Reich, Steve’s use of repetition starts to invoke African kora players, building wave upon wave of hypnotic riffs which slowly mutate. And, like the Velvets, Steve is a master at using space, silence and single-key drones to hammer home his points. Half of this album sees Steve Wold move away from his one-man-band USP by plugging in his guitar and tentatively collaborating with other musicians. “Just Like A King” is a majestic duet with Nick Cave, with backing from Cave’s slob-blues outfit Grinderman, where Cave adds a certain sadistic streak to Steve’s masochistic, lovelorn lyrics. Steve also employs a percussionist, Dan Magnussen from his old backing outfit the Level Devils. He sounds less convincing on tracks like “St Louis Slim” where he plays a full drum kit, but much more effective when he keeps things simple and merely replicates Seasick Steve’s footstomps, like on the gloriously shambolic “Prospect Lane” and “One True”, where the drums sound like they’re being played by a one-man-band wrestling with a bass drum strapped to his back and banging cymbals between his knees. It all proves that Seasick Steve is at his strongest when he’s playing solo. The yearning love song “Walking Man” sees his bottleneck guitar accompanied only by a stomping foot, the singer’s solitude adding weight to the desperate, lovelorn lyric. “When you say jump I say how high”, he croons, a reminder that blues music’s “loser” status can teach Morrissey a thing or two about melancholy. Better still are the slow, ruminative slide guitar tracks like “Fly By Night” and “My Youth”. Here the wayward tempo – which speeds up and slows down to suit the delivery of the lyrics – has the effect of slowing down time and space, to the point that you feel you’re having some out-of-body experience in a hot southern swamp. Best of all is the hypnotic guitar riffs and foot-stomps of “Chiggers”, which is a list of handy tips on how to defeat the bugs of the same name (it involves “pulling your socks up to your knees” and “washing your clothes on the hottest cycle”). “I’m gonna play it on this NASTY gee-tar that I should’ve thrown away a long time ago,” he apologetically announces in his introduction. Yet it’s exactly those nasty gee-tars that makes his music so thrillingly unique. Seasick Steve moves away from them at his peril. JOHN LEWIS Q&A: Seasick Steve: Where did you record the album? It was a residential studio called Leeder’s Farm, in Spooner Row, Norfolk, run by a guy called Dan – real nice fella – who used to be in The Darkness. I liked it cos I could stay in one of the rooms there while I was recording. I spend so much time in England that I’ve decided to move to Norfolk with my family – I just got my wife to quit her horrible job in an old people’s home in Norway. You seem to be collaborating a bit more on this album. Why? It’s just a little boring playing on my own! There’s Nick Cave and his band. They came up to Norfolk on the train, dressed to kill, in their suits and everything! And we got these gospel backing singers from Tennessee on two tracks. Dan Magnussen is the only drummer that I really like to work with – he doesn’t even sound like a drummer, he sounds like his rattling a bag of bones or something! Do you think your blues uses irregular time metres, rather like the earliest Delta bluesman? That’s cos I can’t count! But you’re right. Guys like Robert Johnson and Charley Patton, they didn’t give a shit about whether it was 12 bars or not. They made it up as they went along. At some point I realised that it was okay not to give a shit about it -- I’m not sure the old guys gave a shit, so why should I? INTERVIEW: JOHN LEWIS

There’s a song on this, the second album by the veteran, late-flowering blues maverick Seasick Steve, called “Thunderbird”. Delivered in a gravel-voiced holler that recalls Tom Waits and a series of twisted southern vowels that resemble Dr John, the song is a hymn to the cheapo fortified wine of the same name, a drink that’s popular with both grizzled hobos and students alike.

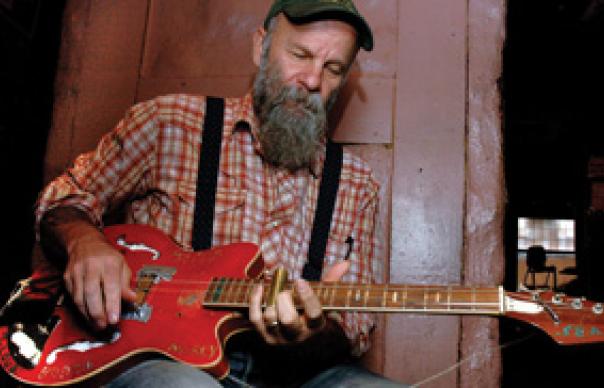

Rather fittingly, it appears to be students and grizzled hobos that comprise Seasick Steve’s core audience. Somehow, the sixtysomething guitarist and singer born Steve Wold has managed to resurrect and reinvent that long debased artform known as the blues, reclaiming it from the dreary boogie revivalists and finding a way of selling it to audiences brought up on The White Stripes.

He’s done this primarily by reconnecting the blues to its earliest solo incarnations, the music of Robert Johnson and Charlie Patton. Part of the reason why those early kings of the delta sound so haunted and ethereal today is because – unhampered by drummers of bass players – they didn’t follow such rigid, 12-bar-blues templates. A cycle might last 12 bars but it might just as easily be 11, 13 or 14 or 22 bars long, and they’d often switch time signature at random. Rarely would they use the same three-chord turnarounds: sometimes they’d play in a single key, or use weird chromatic chord changes.

Seasick Steve does all of this, and his one-man-band status also allows him to explore a more wayward tributary of the Mississippi – one in which Robert Johnson’s solo voyages merge with the avant garde soundscapes of Moondog, the minimalism of Steve Reich and the drone rock of the Velvet Underground. Like Moondog, Steve tries to recreate the sounds in his head by inventing his own mutant instruments (indeed, Steve’s three-stringed “piece of shit” Tranz Wonder guitar is not dissimilar from Moondog’s three-string Oo-yat-su). Like Reich, Steve’s use of repetition starts to invoke African kora players, building wave upon wave of hypnotic riffs which slowly mutate. And, like the Velvets, Steve is a master at using space, silence and single-key drones to hammer home his points.

Half of this album sees Steve Wold move away from his one-man-band USP by plugging in his guitar and tentatively collaborating with other musicians. “Just Like A King” is a majestic duet with Nick Cave, with backing from Cave’s slob-blues outfit Grinderman, where Cave adds a certain sadistic streak to Steve’s masochistic, lovelorn lyrics. Steve also employs a percussionist, Dan Magnussen from his old backing outfit the Level Devils. He sounds less convincing on tracks like “St Louis Slim” where he plays a full drum kit, but much more effective when he keeps things simple and merely replicates Seasick Steve’s footstomps, like on the gloriously shambolic “Prospect Lane” and “One True”, where the drums sound like they’re being played by a one-man-band wrestling with a bass drum strapped to his back and banging cymbals between his knees.

It all proves that Seasick Steve is at his strongest when he’s playing solo. The yearning love song “Walking Man” sees his bottleneck guitar accompanied only by a stomping foot, the singer’s solitude adding weight to the desperate, lovelorn lyric. “When you say jump I say how high”, he croons, a reminder that blues music’s “loser” status can teach Morrissey a thing or two about melancholy. Better still are the slow, ruminative slide guitar tracks like “Fly By Night” and “My Youth”. Here the wayward tempo – which speeds up and slows down to suit the delivery of the lyrics – has the effect of slowing down time and space, to the point that you feel you’re having some out-of-body experience in a hot southern swamp.

Best of all is the hypnotic guitar riffs and foot-stomps of “Chiggers”, which is a list of handy tips on how to defeat the bugs of the same name (it involves “pulling your socks up to your knees” and “washing your clothes on the hottest cycle”). “I’m gonna play it on this NASTY gee-tar that I should’ve thrown away a long time ago,” he apologetically announces in his introduction. Yet it’s exactly those nasty gee-tars that makes his music so thrillingly unique. Seasick Steve moves away from them at his peril.

JOHN LEWIS

Q&A: Seasick Steve:

Where did you record the album?

It was a residential studio called Leeder’s Farm, in Spooner Row, Norfolk, run by a guy called Dan – real nice fella – who used to be in The Darkness. I liked it cos I could stay in one of the rooms there while I was recording. I spend so much time in England that I’ve decided to move to Norfolk with my family – I just got my wife to quit her horrible job in an old people’s home in Norway.

You seem to be collaborating a bit more on this album. Why?

It’s just a little boring playing on my own! There’s Nick Cave and his band. They came up to Norfolk on the train, dressed to kill, in their suits and everything! And we got these gospel backing singers from Tennessee on two tracks. Dan Magnussen is the only drummer that I really like to work with – he doesn’t even sound like a drummer, he sounds like his rattling a bag of bones or something!

Do you think your blues uses irregular time metres, rather like the earliest Delta bluesman?

That’s cos I can’t count! But you’re right. Guys like Robert Johnson and Charley Patton, they didn’t give a shit about whether it was 12 bars or not. They made it up as they went along. At some point I realised that it was okay not to give a shit about it — I’m not sure the old guys gave a shit, so why should I?

INTERVIEW: JOHN LEWIS