The Python catalogue, repackaged and remastered. Lovely plumage... Given their strong group identity, and their friendship with George Harrison, it’s not hard to see how the Monty Python has come to be known as “the Beatles of comedy”. Really, though, if we seek comparables for Python, we need other names. Their work, like The Who’s, has spawned a West End musical. Their catalogue has been reissued and compiled as often as that of Jimi Hendrix. Most recently, like Led Zeppelin, they’ve announced plans to regroup, and, dead member notwithstanding, play London’s O2 Arena. They didn’t stress the association, but Python learned a lot from rock’s example. They toured as a band would, airing half new stuff, half “old favourites”. They recorded live albums (like 1974’s enjoyable Live At Drury Lane). Most impressively, they understood what many musicians of the era did not: that the joy of the enterprise would decrease with obligation. They split early, the better to regroup afresh. “That way,” John Cleese explained in a 1974 interview included here, “Python could go on almost indefinitely.” So now for something essentially the same. Namely: a box set of Monty Python’s remastered audio work, the nine albums they released over ten years, from their eponymous 1970 debut live album (the eerily unlive-sounding Monty Python’s Flying Circus), all the way to 1980’s Contractual Obligation Album. Albums for Python were arguably more revenue streams than a gateway to a new medium, but they certainly weren’t (for all their ironic titling) rip-offs. In a pre-VHS world, the idea of a record of sketches from the TV show must have been an attractive proposition, while most featured new or reworked material from the TV broadcasts. Though funny, this was still material filled with the strong currents of the time. The same age as Jagger, McCartney and Townshend, Monty Python was no more inclined than the Stones, Who (or indeed Beatles), to conform to a Britain stifled by authority, bureaucracy, and prudery. Rather than become part of the establishment – which, with their university educations, might have welcomed them – they instead undermined its failings, using its own high culture and privileged information against it. Acutely aware of the format in which it appeared, Python’s satire of TV, from current affairs to cultural discussion and game shows (“In the event of a tie, I’ll start the clock”) gave you to understand that no broadcast was worthy of your trust. In a pre-internet world, they democratized their knowledge: from philosophical terms to British history and the machinery of government, to fish sauces and esoteric cheese. Ten million viewers stayed up til 11pm on Sunday night to watch it. Python on record is probably more about the greatest hits (“Dead Parrot” and other undergraduate recitables have been compiled on several albums; there is one – Sings…. – dedicated to their many songs), but even in a format that was not entirely theirs, there’s no repressing Python’s ingenuity. As on TV, here they were very aware of their medium. The 1975 Holy Grail record, for example, begins with an explanation of the LP’s expensive “Executive Edition”, an ironic moment during this deluxe box set. One wonders, in fact, if they’ve missed a trick by not calling this The Entirely Unnecessary Remasters. 1973’s Matching Tie And Handkerchief, echoing the excesses of rock LPs of the period, featured elaborate fold-out art by Terry Gilliam and a “concentric groove” vinyl master by George “Porky” Peckham. Today, some inevitably play better than others. In spite of their extra material the film soundtracks are just that – draughty-sounding excerpts of good bits, superfluous in the present age of home media. The Contractual Obligation Album, featuring a disproportionately large number of songs (“Never Be Rude To An Arab” and so on), is tough to get through, though it is nearly redeemed by “Rock Notes”, a magnificent parody of 1960s music journalism. Considered alone, it’s probably an album like the consistently amusing Previous Record (1972) that’s the best, not least for showing its self-knowledge. When Flying Fox of the Light Entertainment Police arrives to arrest the team for offences under the Strange Sketch Act, it’s clear Monty Python has reached a post-modern tipping point, and needs to move to bigger challenges. “Silly” is a word that Pythons use often to describe their work, and their best comedy is certainly, heartwarmingly, that. Really, though, it seems a little modest. With its combination of eloquent sedition, manic energy and occasional profanity, their work doesn’t seem much short of revolutionary. John Robinson

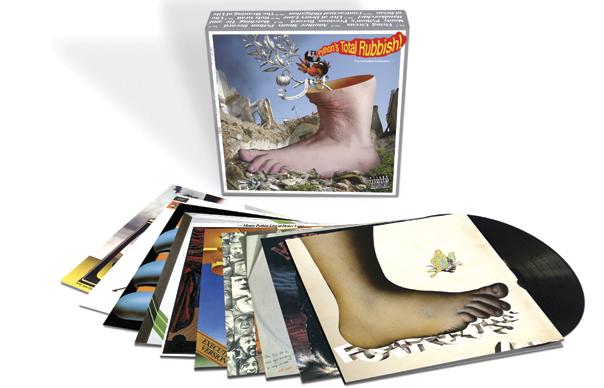

The Python catalogue, repackaged and remastered. Lovely plumage…

Given their strong group identity, and their friendship with George Harrison, it’s not hard to see how the Monty Python has come to be known as “the Beatles of comedy”. Really, though, if we seek comparables for Python, we need other names. Their work, like The Who’s, has spawned a West End musical. Their catalogue has been reissued and compiled as often as that of Jimi Hendrix. Most recently, like Led Zeppelin, they’ve announced plans to regroup, and, dead member notwithstanding, play London’s O2 Arena.

They didn’t stress the association, but Python learned a lot from rock’s example. They toured as a band would, airing half new stuff, half “old favourites”. They recorded live albums (like 1974’s enjoyable Live At Drury Lane). Most impressively, they understood what many musicians of the era did not: that the joy of the enterprise would decrease with obligation. They split early, the better to regroup afresh. “That way,” John Cleese explained in a 1974 interview included here, “Python could go on almost indefinitely.”

So now for something essentially the same. Namely: a box set of Monty Python’s remastered audio work, the nine albums they released over ten years, from their eponymous 1970 debut live album (the eerily unlive-sounding Monty Python’s Flying Circus), all the way to 1980’s Contractual Obligation Album. Albums for Python were arguably more revenue streams than a gateway to a new medium, but they certainly weren’t (for all their ironic titling) rip-offs. In a pre-VHS world, the idea of a record of sketches from the TV show must have been an attractive proposition, while most featured new or reworked material from the TV broadcasts.

Though funny, this was still material filled with the strong currents of the time. The same age as Jagger, McCartney and Townshend, Monty Python was no more inclined than the Stones, Who (or indeed Beatles), to conform to a Britain stifled by authority, bureaucracy, and prudery. Rather than become part of the establishment – which, with their university educations, might have welcomed them – they instead undermined its failings, using its own high culture and privileged information against it.

Acutely aware of the format in which it appeared, Python’s satire of TV, from current affairs to cultural discussion and game shows (“In the event of a tie, I’ll start the clock”) gave you to understand that no broadcast was worthy of your trust. In a pre-internet world, they democratized their knowledge: from philosophical terms to British history and the machinery of government, to fish sauces and esoteric cheese. Ten million viewers stayed up til 11pm on Sunday night to watch it.

Python on record is probably more about the greatest hits (“Dead Parrot” and other undergraduate recitables have been compiled on several albums; there is one – Sings…. – dedicated to their many songs), but even in a format that was not entirely theirs, there’s no repressing Python’s ingenuity. As on TV, here they were very aware of their medium. The 1975 Holy Grail record, for example, begins with an explanation of the LP’s expensive “Executive Edition”, an ironic moment during this deluxe box set. One wonders, in fact, if they’ve missed a trick by not calling this The Entirely Unnecessary Remasters. 1973’s Matching Tie And Handkerchief, echoing the excesses of rock LPs of the period, featured elaborate fold-out art by Terry Gilliam and a “concentric groove” vinyl master by George “Porky” Peckham.

Today, some inevitably play better than others. In spite of their extra material the film soundtracks are just that – draughty-sounding excerpts of good bits, superfluous in the present age of home media. The Contractual Obligation Album, featuring a disproportionately large number of songs (“Never Be Rude To An Arab” and so on), is tough to get through, though it is nearly redeemed by “Rock Notes”, a magnificent parody of 1960s music journalism. Considered alone, it’s probably an album like the consistently amusing Previous Record (1972) that’s the best, not least for showing its self-knowledge. When Flying Fox of the Light Entertainment Police arrives to arrest the team for offences under the Strange Sketch Act, it’s clear Monty Python has reached a post-modern tipping point, and needs to move to bigger challenges.

“Silly” is a word that Pythons use often to describe their work, and their best comedy is certainly, heartwarmingly, that. Really, though, it seems a little modest. With its combination of eloquent sedition, manic energy and occasional profanity, their work doesn’t seem much short of revolutionary.

John Robinson