Arthur Lee was a famously mercurial bandleader. He turned down the Monterey Pop Festival, Woodstock and the Ed Sullivan Show, believing his music should have top billing or none at all. His hardline go-it-alone policy ensured Love’s cult status for all time. But he was as chaotic as he was dogmatic: he once sacked a Love guitarist (Jay Donnellan) for suggesting the band should aim to arrive at gigs more promptly – or at least on the day they were scheduled to take place – and those kind of old habits die hard. At London’s Highbury Garage in 1994, Lee went AWOL minutes before he was due onstage. A search party found him playing pool in a pub on the Holloway Road, oblivious to the panic he was causing.

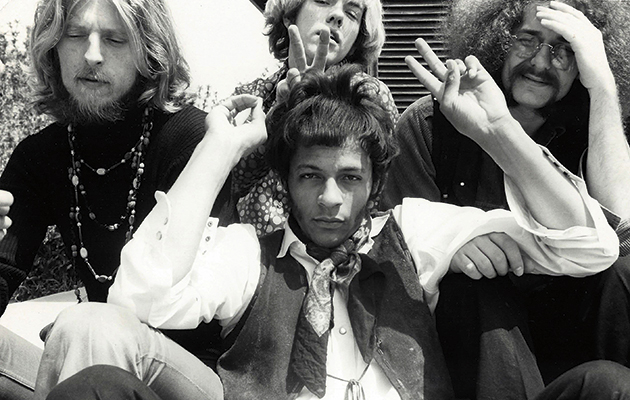

A life lived by its own rules can be a frustrating one to compile for posterity. No live recordings circulate of Love from the ’60s – their heyday of Da Capo and Forever Changes – because Lee wouldn’t permit concerts to be taped. Coming Through To You, a 4CD boxset that attempts to document the best of what’s out there, has no choice but to begin in 1970, when the classic Love lineup had disintegrated and a new Love was exploring a heavier direction. That February, Lee allowed them to share a Fillmore East bill with the Grateful Dead and The Allman Brothers; the next stop was England, where fans expecting the beatific splendour of Forever Changes had to adjust to a long-haired Love more reminiscent of Hendrix’s “Crosstown Traffic”.

Eight of the 14 songs on the first disc have been released before – either on Studio/Live (1982) or The Blue Thumb Recordings (2007) – but six from Copenhagen and the Fillmore West, while known to bootleggers, are previously unissued. None would score high on subtlety. Sensitive listeners may quail at a turbo-charged “Bummer In The Summer” (at Waltham Forest Technical College), but that’s got to be better, surely, than Lee’s off-key caterwauling on “Good Times” in Denmark a fortnight later. As for his grunts and screeches at the Fillmore West, he sounds like he wishes he was fronting Steppenwolf.

The vicissitudes of a stop-start career meant that the 1980s were virtually a write-off for Lee. We next encounter him at the BBC in 1992, promoting a comeback album (Arthur Lee & Love – Five String Serenade) with an acoustic session for Radio 1’s Richard Skinner. Feted by a new generation, Lee would see his fortunes improve. Disc Two follows him on the promo trail to Amsterdam (for a shaky “Alone Again Or” and a half-remembered “Hey Joe”) and to 1993 and 1996 gigs in Massachusetts and Odense. Close-up microphones intrude on every faltering guitar chord (“Signed D.C.”), but they also bear witness to Lee’s rediscovery of his golden voice. That majestic, heavenly warble! This, we sense, is a vision of the old Arthur. When a young flautist is brought onstage for “She Comes In Colors” – the 48-year-old Lee was happy to revisit Da Capo by 1993, much to the audience’s delight – her songbird trills seem to sing of a musical renaissance. “7 & 7 Is”, tackled at thrilling speed in Odense, is further evidence of a prodigal return. Within months, however, Lee was in a California prison, gaoled for illegally discharging a firearm. His 12-year sentence symbolised his career: three strikes and you’re out.

Re-emerging in 2001 after an appeals court reversed the charge, Lee entered a new phase of his life in which he enjoyed near-heroic status among fans of ’60s psychedelia. Disc Three sees him at Glastonbury (a lovely “Andmoreagain”) and Roskilde, backed by Baby Lemonade – an LA psych quartet – and a chamber orchestra. Familiar with every note of Forever Changes, Baby Lemonade were able to pull off uncanny renditions of “The Daily Planet”, “Old Man” and “You Set The Scene” as if they’d played on the originals. Finally, Love’s recondite masterpiece became the hot-ticket, must-see attraction it should have been in 1968.

If the first three discs comprise good-to-very-good sound quality, Disc Four takes us into the crowd for 16 hand-held recordings from 12 gigs spanning 27 years. Opening with a 1977 harmonica solo (bewildering and brief), it wanders from blues improv to Hendrix cover (“Little Wing”) via – of all things – reggae. Ultimately it finds its way to “Rainbow In The Storm”, from Love’s final EP (“Love On Earth Must Be”, 2004), performed in Wrexham. The sound may lack fidelity, but the tapes are not short on historical significance. At the Whisky A Go Go in 1978, Lee is reunited with Bryan MacLean (who sounds wasted), while an extended “Smokestack Lightning”, from 2003, features Love’s classic-era guitarist John Echols and – incredibly – their first drummer Don Conka, subject of the immortal “Signed D.C.”. It’s a decent jam, too.

When the boxset ends in April 2004 (“Singing Cowboy”, Shepherd’s Bush Empire), Lee has become the reliable, punctual, globe-trotting artist he never set out to be, playing to the adoring fans he was too imperious to reach the first time round. Sadly, his rebirth couldn’t last. He succumbed to an acute strain of leukaemia in 2006 at the age of 61. Conka (in 2004) and MacLean (1998) had already preceded him.

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.