Mali has become the country impossible to ignore. Always one of the continent's musical power-houses, the West African nation has been an omnipresent factor in African music's inexorable ascent over the past 30 years. Where other cultures have faded in and out, Mali has stayed a constant. Early on it was the '80s synths and soaring vocals of Salif Keita that flew the flag. More recently the exuberant duets of Amadou & Mariam, the feminist chamber pop of Rokia Traore, the hypnotic desert blues of Tinariwen and the wild ngoni fretboards of Bassekou Kouyate have all won international acclaim, helped along by Damon Albarn's evangelising. The clanging electric blues of Ali Farka Toure and the rippling kora of Toumani Diabate have been complementary forces throughout Mali's campaign to be heard. Toure's early releases, in the late '70s, were fallen on by European cognoscenti with astonishment - they were familiarly bluesy yet quite distinct from the American traditions they clearly shared. Diabate, a generation younger, arrived a decade later, immediately showing the crossover potential of the melodic kora by collaborating with flamenco group Ketama. It was thanks to their shared producer, Nick Gold, of pioneering label World Circuit, that Toure and Diabate finally worked together, recording the much garlanded In The Heart Of The Moon in a disused Bamako hotel in 2004. By then, both men had become international stars, their albums awarded Grammies and their talents sought out for groundbreaking collusions. Toure had playing alongside Ry Cooder and Taj Mahal, while Diabate had worked with Bjork, Albarn and Roswell Rudd. That the pair hadn't previously played together isn't so surprising. Age difference aside, they represent two very different strands of Malian culture. Toure belongs to the country's north, growing up 'a child of the river' and later acquiring a farm on the banks of the Niger. Self-taught, much inspired by the R'n'B he encountered as a young man - he was for years described as "Africa's John Lee Hooker", which irked both bluesmen no end - Toure etched out his own variation on Mali's traditions, the music Martin Scorsese has called "the DNA of the blues". Diabate, by contrast, is from the lusher south, a former child prodigy, born into a clan of griots, who can trace his lineage back 70 generations. The traditions of the kora, the 21-string African harp, are more ancient still, akin to the lore surrounding the sitar; both kora and sitar are considered sacred instruments, though both have nonetheless found their way into western pop. The impromptu London sessions that produced Ali & Toumani were to prove Toure's last - he died the following year, 2006. Since then Diabate has been busy. Following the Grammy award he received for In The Heart Of The Moon, he released Boulevard de L'Independence with his Symmetric Orchestra, then an inspired solo set, The Mande Variations, both pushing back the release of this current album. Diabate has created two laments to the fallen Mali blues maestro, once on The Mande Variations, and again with Vieux Farka Toure, Ali's son, on his eponymous debut. Vieux is himself a force to be reckoned with, one of a new generation destined to further internationalise African traditions; he's already dabbled with funk, reggae and remixes. His father's reputation has posthumously grown, helped by the rise of Tinariwen, whose own desert blues owe a clear debt to Toure's innovations. Toure's part in Ali & Toumani is some way from the pungent electric blues for which he is mostly celebrated, the music that blazed from his early Green and Red LPs or from later creations like The River. Here he offers a rhythmic backdrop of picked acoustic guitar - flowing as inexorably as his beloved river - against which Diabate's kora dances. It's a simple formula but it works brilliantly. One reason why is that Diabate adds more than the dazzling cascades of notes that first catch the ear. Part of Diabate's fame is founded on his ability to play rhythm, bass and melody lines simultaneously (thus turning the kora into a solo instrument for the first time), and here he regularly returns from his improvised flights to restate a number's basics alongside Toure. Try the twinkling "56", for example: the effect is to make the duo sound more like a trio. Almost all instrumental, with the occasional comment or chorus from Toure, the LP works, like its predecessor, as much through its mesmeric ambience as its hooklines. "Sabu Yerkoy" is the clear exception, with its call-and-response vocals, its stalking salsa rhythm, discreet drums and an elastic bassline provided by Cachaito Lopez, of Buena Vista Social Club fame, for whom this would also be a final session (he died in 2009). It's a charmer that reminds us of the transatlantic musical exchange that saw Africa's music exported with slavery, only for it to return and conquer centuries on when Cuban salsa became hugely popular in West Africa during the '50s and '60s. By contrast, "Be Mankan" is a stately, almost classical piece for kora, as is the more nimble "Fantasy". "Doudou" is a trance-out on which the two sets of strings gallop together, while "Warbe" is the bluesiest item here. With Toure more to the fore, both he and Diabate teasing out lines that wouldn't sound out of place in a Robert Johnson or Freddie King solo, it's pure alchemy. "Machengoida" offers a more austere, considered line of blues, with the duo taking it in turns to explore a simple, descending melody line in endless, varied detail. "Kalu Dja", the closer, is also the 'single' that will preface Ali & Toumani. It's a chiming, accessible piece that's emblematic of the album's rapport and spirit without being its stand-out. Such considerations scarcely apply, in any case, to a record that works by cumulative power, and whose approach lies somewhere between an acoustic jam session and a Ravi Shankar raga. Aside from being an album of spellbinding beauty, Ali & Toumani is also a posthumous valediction to Ali Farka Toure, and an affirmation that from Mali there is surely much more to come. Neil Spencer

Mali has become the country impossible to ignore. Always one of the continent’s musical power-houses, the West African nation has been an omnipresent factor in African music’s inexorable ascent over the past 30 years.

Where other cultures have faded in and out, Mali has stayed a constant. Early on it was the ’80s synths and soaring vocals of Salif Keita that flew the flag. More recently the exuberant duets of Amadou & Mariam, the feminist chamber pop of Rokia Traore, the hypnotic desert blues of Tinariwen and the wild ngoni fretboards of Bassekou Kouyate have all won international acclaim, helped along by Damon Albarn‘s evangelising.

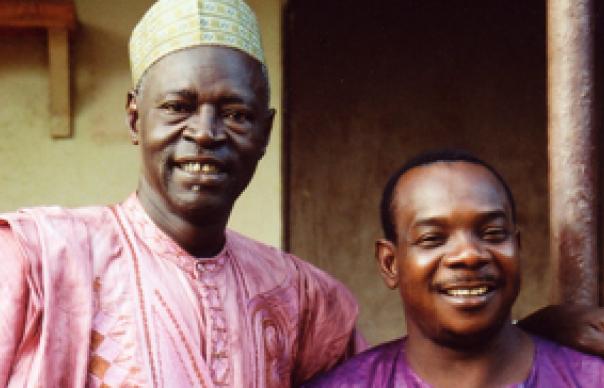

The clanging electric blues of Ali Farka Toure and the rippling kora of Toumani Diabate have been complementary forces throughout Mali’s campaign to be heard. Toure’s early releases, in the late ’70s, were fallen on by European cognoscenti with astonishment – they were familiarly bluesy yet quite distinct from the American traditions they clearly shared. Diabate, a generation younger, arrived a decade later, immediately showing the crossover potential of the melodic kora by collaborating with flamenco group Ketama.

It was thanks to their shared producer, Nick Gold, of pioneering label World Circuit, that Toure and Diabate finally worked together, recording the much garlanded In The Heart Of The Moon in a disused Bamako hotel in 2004. By then, both men had become international stars, their albums awarded Grammies and their talents sought out for groundbreaking collusions. Toure had playing alongside Ry Cooder and Taj Mahal, while Diabate had worked with Bjork, Albarn and Roswell Rudd.

That the pair hadn’t previously played together isn’t so surprising. Age difference aside, they represent two very different strands of Malian culture. Toure belongs to the country’s north, growing up ‘a child of the river’ and later acquiring a farm on the banks of the Niger. Self-taught, much inspired by the R’n’B he encountered as a young man – he was for years described as “Africa’s John Lee Hooker“, which irked both bluesmen no end – Toure etched out his own variation on Mali’s traditions, the music Martin Scorsese has called “the DNA of the blues”.

Diabate, by contrast, is from the lusher south, a former child prodigy, born into a clan of griots, who can trace his lineage back 70 generations. The traditions of the kora, the 21-string African harp, are more ancient still, akin to the lore surrounding the sitar; both kora and sitar are considered sacred instruments, though both have nonetheless found their way into western pop.

The impromptu London sessions that produced Ali & Toumani were to prove Toure’s last – he died the following year, 2006. Since then Diabate has been busy. Following the Grammy award he received for In The Heart Of The Moon, he released Boulevard de L’Independence with his Symmetric Orchestra, then an inspired solo set, The Mande Variations, both pushing back the release of this current album. Diabate has created two laments to the fallen Mali blues maestro, once on The Mande Variations, and again with Vieux Farka Toure, Ali’s son, on his eponymous debut. Vieux is himself a force to be reckoned with, one of a new generation destined to further internationalise African traditions; he’s already dabbled with funk, reggae and remixes. His father’s reputation has posthumously grown, helped by the rise of Tinariwen, whose own desert blues owe a clear debt to Toure’s innovations.

Toure’s part in Ali & Toumani is some way from the pungent electric blues for which he is mostly celebrated, the music that blazed from his early Green and Red LPs or from later creations like The River. Here he offers a rhythmic backdrop of picked acoustic guitar – flowing as inexorably as his beloved river – against which Diabate’s kora dances.

It’s a simple formula but it works brilliantly. One reason why is that Diabate adds more than the dazzling cascades of notes that first catch the ear. Part of Diabate‘s fame is founded on his ability to play rhythm, bass and melody lines simultaneously (thus turning the kora into a solo instrument for the first time), and here he regularly returns from his improvised flights to restate a number’s basics alongside Toure. Try the twinkling “56”, for example: the effect is to make the duo sound more like a trio.

Almost all instrumental, with the occasional comment or chorus from Toure, the LP works, like its predecessor, as much through its mesmeric ambience as its hooklines. “Sabu Yerkoy” is the clear exception, with its call-and-response vocals, its stalking salsa rhythm, discreet drums and an elastic bassline provided by Cachaito Lopez, of Buena Vista Social Club fame, for whom this would also be a final session (he died in 2009). It’s a charmer that reminds us of the transatlantic musical exchange that saw Africa’s music exported with slavery, only for it to return and conquer centuries on when Cuban salsa became hugely popular in West Africa during the ’50s and ’60s.

By contrast, “Be Mankan” is a stately, almost classical piece for kora, as is the more nimble “Fantasy”. “Doudou” is a trance-out on which the two sets of strings gallop together, while “Warbe” is the bluesiest item here. With Toure more to the fore, both he and Diabate teasing out lines that wouldn’t sound out of place in a Robert Johnson or Freddie King solo, it’s pure alchemy. “Machengoida” offers a more austere, considered line of blues, with the duo taking it in turns to explore a simple, descending melody line in endless, varied detail.

“Kalu Dja”, the closer, is also the ‘single’ that will preface Ali & Toumani. It’s a chiming, accessible piece that’s emblematic of the album’s rapport and spirit without being its stand-out. Such considerations scarcely apply, in any case, to a record that works by cumulative power, and whose approach lies somewhere between an acoustic jam session and a Ravi Shankar raga. Aside from being an album of spellbinding beauty, Ali & Toumani is also a posthumous valediction to Ali Farka Toure, and an affirmation that from Mali there is surely much more to come.

Neil Spencer