Linda Peters and Richard Thompson’s partnership began with a dreadful conversation in a Chelsea restaurant, and ended with the ‘tour from hell’, car theft and an arrest. In between, there were those experiences common to most relationships. You know the sort: marriage, children, six poorly selling albums and more than a year in a couple of intense Sufi Muslim communities.

Hard Luck Stories attempts to catalogue, across eight CDs, this fragile decade the Thompsons spent together and all that they created in that tumultuous time. Inside there’s one masterpiece and three very fine records, all remastered. There are also two albums disowned by their creators and reissued here for the first time in almost 30 years, along with demos and live tracks.

The Thompsons came from folk-rock, of course, with the couple first meeting at the sessions for Fairport Convention’s monumental Liege & Lief at London’s Sound Techniques studio in late 1969. But despite the occasional dabble with accordions and crumhorns, the duo’s material was all Richard’s own, oscillating between earthy misanthropy and devotional hymns. Whatever the content, Linda sang with a beautifully sad, ageless poise, her deep voice neither as unadorned as Shirley Collins or the Watersons’, nor as high and clear as Maddy Prior or Jacqui McShee’s.

Their first tours in late 1972 found the pair visiting dreary folk clubs, Linda driving as Richard couldn’t, their rare go at trad-arr material represented here by a strident “Napoleon’s Dream”, Richard puffing as if he’s just run from Cecil Sharp House to the Rainbow. His solo debut, April’s Henry The Human Fly, had featured Linda, and a couple of those tracks also appear on the ‘early years’ disc, along with rock’n’roll numbers the pair covered as part of supergroup The Bunch – Linda and Sandy Denny’s take on the Everlys’ “When Will I Be Loved” is a keeper.

None of the Thompsons’ previous work hinted at the majesty of their debut, 1974’s I Want To See The Bright Lights Tonight, a stately dive into melancholy depths. There’s a sublime restraint to these 10 songs, from Linda’s vocals and Richard’s guitar (the latter biting only on “When I Get To The Border” and “The Calvary Cross”) to a measured rhythm section of Timmy Donald and Pat Donaldson. The drums dissolve completely for the closing “The Great Valerio”, its gothic mood matched by the acoustic guitar’s sour chords and a snatch of Satie’s ghostly “La Balançoire” to close.

As on most of Hard Luck Stories, the remastering is barely noticeable, but the previously unreleased bonus tracks are more notable: “Mother & Son”, the Thompsons harmonising over an awkward piano tune, is a throughline from the more ghoulish parts of Henry The Human Fly; a sparse early take of “Down Where The Drunkards Roll” shows just how fluid Linda’s vocal inflections could be; while “The End Of The Rainbow”, here sung by Linda instead of Richard, is a peek at an alternate universe. None of these tracks merit inclusion on the original LP, but it’s fascinating to hear their development.

Hokey Pokey (1975) continued their twisted brand of joie de vivre, but added bleak gallows humour. Even when things start off well for the protagonists, as in “Georgie On A Spree”, there’s a certainty that illness or heartbreak will soon reduce them to the penury of the people “writhing around in the mud” on “The Sun Never Shines On The Poor”. Yet the Thompsons assure us that being “poor in the heart” is “the worst kind of poor you can be”, which lays the path for the same year’s Pour Down Like Silver. The duo had already found religion – see Hokey Pokey’s “A Heart Needs A Home” – but now they were adorned in some top Sufi gear on the cover and were singing thinly veiled hymns to God. The sorrowful rapture of “Night Comes In”, inspired by the whirling Sufi dervishes, is almost post-rock in its quietude, with Richard’s multi-tracked solos spiralling off into the perfumed dark. Here the LP’s joined by some unheard outtakes, the grooving “Wanted Man” and “Last Chance”, which shows that even a singer as peerless as Linda had the odd off-day.

The fifth disc, The Madness Of Love, is the box’s greatest new treasure, starting off with six live acoustic songs from London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall in April 1975, including the plaintive “Never Again”. After spending 1976 in various Muslim communities, the Thompsons returned with an all-Sufi band to showcase brand-new songs on a May ’77 tour; inspired by Islamic scripture and poetry, few of these songs were ever recorded, but their live versions appear here. While they can’t match, say, “Withered And Died”, the soulful “The King Of Love” and the mellifluous “A Bird In God’s Garden” have a sound that would have been worth exploring further. Droning and packed with percussion and electric piano, they’re more funk-fusion than folk-rock, and as heavy and heady as the scent of Arabian oud. We also get “an old one”, a stunning 13-minute “Night Comes In”, this time exquisitely sung by Linda.

The Thompsons’ most controversial records, 1978’s First Light and 1979’s Sunnyvista, both on Chrysalis, are reissued here for the first time in decades. The couple were sharing studios with the Banshees, but First Light possesses little punk vigour. Tracked with crack US sessioneers, it’s syrupy and confused: at one point, smooth ballad “Sweet Surrender” is followed by the quasi-disco “Don’t Let A Thief Steal Into Your Heart” and then the trad instrumental “The Choice Wife”. The agitated “Layla”, however, is a highlight, as is “Pavanne”, a rare co-write that recaptures the magic of their doomy early ballads. Sunnyvista features attempts at cajun (“Saturday Rolling Around”) and cabaret (the title track) that could only be described as ill-advised, and a take on reggae-tinged new wave (“Civilisation”) that somehow succeeds. “Justice In The Streets”, meanwhile, is bastardised funk with a Middle Eastern or North African twist – it should be terrible, but it ends up sounding, rather pleasantly, like Tinariwen or Tamikrest.

Arabic funk isn’t the fastest route to the hit parade, though, and Chrysalis, expecting commercial success, dropped the pair. Enter Gerry Rafferty, a man who knew a bit about folkies becoming pop stars, to fund and produce new sessions in 1980. Six of the results are featured here, but frustratingly not everything on the Rafferty’s Folly bootleg or what’s now on YouTube. A missed opportunity for completists, for sure, even if the fruits of the Rafferty sessions are generally (save a devastating “Walking On A Wire”) inferior to the re-recordings on 1982’s Shoot Out The Lights. The vibe is back-to-basics, so there are no fusion jams or hints of reggae – just eight vaguely folky rock songs that might have appeared on vintage Fairport LPs without too much adjustment, and are all the better for it.

“Let me ride on the wall of death one more time,” the pair sang on Shoot Out The Lights’ triumphant closer, “Wall Of Death”. There would be no more trips, though, with Richard leaving a pregnant Linda as 1983 dawned. Solo careers ensued, but neither would find a better creative foil or quite re-create the magic of their first three albums together.

After the split, of course, there was one grim footnote: a 1983 US tour that the pair were strong-armed into honouring. Linda, self-medicating with drink and pills to get through her struggles with dysphonia, at one point even stole a car and found herself at a Niagara police station. Infamously, she would kick her teetotal husband in the shins while he soloed. On the strength of “Pavanne”, one of two songs included from an Indiana gig, she was at least in fine form at the mic.

Aside from some hurried thanks, the last voice heard on Hard Luck Stories’ final track, a raucous cover of Jerry Lee Lewis’s “High School Confidential”, is Linda’s: she’s lost in rapture – one undoubtedly musical and chemical rather than religious – whooping exultantly as the song tumbles to a close. Richard and Linda were over. Long may their work live on.

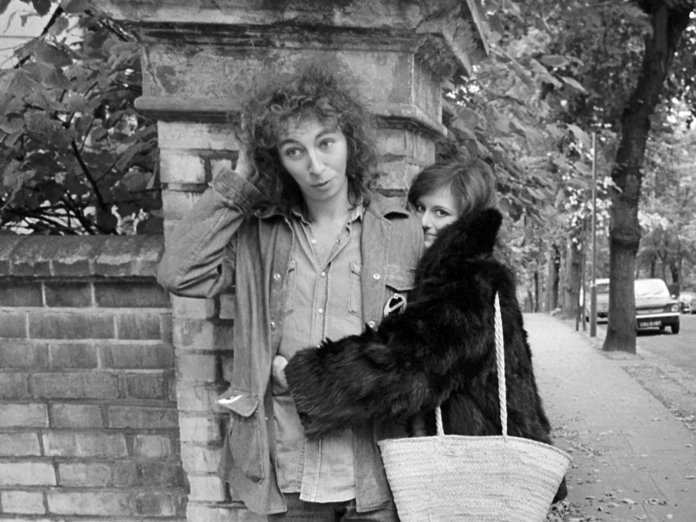

Extras: 8/10. A 72-page hardback book with new essays (and a great deal of formatting and spelling mistakes) and previously unseen photos.