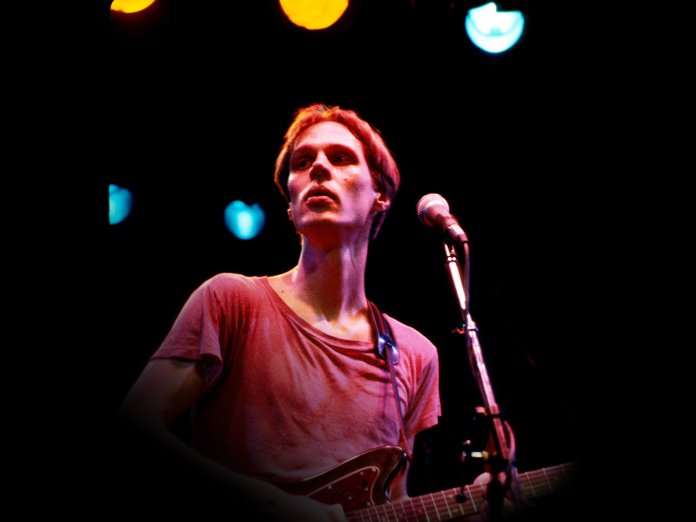

In memory of Tom Verlaine, who has passed away aged 73, Uncut revisits our 2022 feature on Television’s frontman and guitarist.

TV Personality

Forty-five years on, Marquee Moon remains an unassailable classic. But what of TELEVISION’s guiding light, the elusive TOM VERLAINE? Drawing on memories of exacting working methods, Froggy The Gremlin and Television’s unfinished fourth studio album, collaborators and bandmates separate fact from friction. “He’s remained true to himself over all the years,” hears Rob Hughes, “He’s following his instincts.”

In December 2007, Television snuck into the studio to start making a new album. The band spent two or three days recording ideas at New York’s Stratosphere Sound. Sadly, the long-overdue successor to 1992’s Television stalled right there. And hasn’t been touched since.

“We did around 14 things,” reveals guitarist Jimmy Rip. “They don’t have vocals on them and there are no guitar solos, but they’re songs. And some of them are great, I really love them.”

Rip puts in a call to Television leader Tom Verlaine around the same time each year. It’s become something of an in-joke over the past decade or so, a larkish reminder of unfinished business: “In the week between Christmas and New Year, I’ll call Tom up and say happy anniversary. He’ll say, ‘What are you talking about?’ And I’ll go, ‘I’m talking about those tracks!’ But it’s never had any effect. He’s like, ‘Well Jim, some day old Tom will just have it all finished.’”

The prospect of new Television songs, however remote, is a tantalising one. Never mind their slim studio legacy – 1977’s monumental Marquee Moon and luminous successor Adventure, plus that early ‘90s ‘comeback’ – the vitality and significance of their work remains unbroken by the roll of time.

Verlaine’s solo career has followed similar lines. After Television’s initial split in the late ‘70s, he began with a flurry of purpose, continuing deep into the next decade. But he slowed dramatically in the early ‘90s, not long after Television’s brief first reunion. His last solo album arrived in 2006, prompting speculation that New York’s most mercurial guitar hero may have run out of things to say.

“He’s kind of a mystery,” says Sonic Youth’s Lee Ranaldo, who coaxed Verlaine into playing on the soundtrack of Todd Haynes’ 2007 Dylan drama, I’m Not There. “I’ve known Tom for a long time and he’s just one of those guys that’s marching to his own drummer. I’m fascinated by him and what his daily life might be like. Or if he still has goals and ambitions. Like, is he all dried up or is he just circling the wagons and waiting for lightning to strike?”

Songwriter, producer and author Lenny Kaye, Patti Smith’s longtime guitarist, first met Verlaine in 1974. “He’s somewhat guarded,” he observes. “When I think of Tom, I have this image of him smoking a cigarette and peering out through the smoke with this kind of inquisitive gleam in his eye. He’s not an effusive public persona and has never been into putting on the costume of rock stardom. I believe he’s remained pretty true to himself over all the years, just following his instincts.”

The paucity of fresh product makes little difference to Verlaine’s legend, which was secured a long time ago. Television gained traction in the punk milieu of ‘70s New York City, but transcended the scene with their terse, visionary mix of art-rock and spatial jazz. At its heart was chief songwriter Verlaine, whose unique vocal cry was complemented by an angular, precise, explorative guitar style that his sometime lover Patti Smith once memorably likened to “a thousand bluebirds screaming”.

The relationship between Verlaine and co-guitarist Richard Lloyd was too fraught to last. But their remarkably fluid interplay – both live and in the studio, exchanging rhythm and leads – was a thing of rapture. He and Verlaine are estranged, though he’s generous enough to acknowledge his ex-bandmate’s influence.

“He’s an astonishing player,” offers Lloyd, who eventually quit Television in 2007, citing lack of studio activity. “And his lyrics and the way he composed tunes were very different than anybody else. There was a strain between us, but every time we played was a blessed moment. Frankly, the guy was a genius. I just got sick of not recording. I knew we had another album in us.”

Verlaine’s has always moved at his own curious pace. Raised in Delaware, the young Thomas Miller studied piano and played saxophone, to the detriment of formal studies. He befriended Richard Meyers at Sanford Preparatory School, the pair sharing a passion for music, books and poetry. In 1966, aged 16, they both quit school and – recasting themselves as fugitive poets – attempted to hitchhike to Florida. The law caught up with them soon enough.

Meyers finally escaped to New York City after Christmas, while Miller stayed on to finish school. By late ’68, though, he’d dropped out of college in South Carolina to join Meyers in the East Village. They hung out, wrote poetry together, scraped a living working in bookstores and, in 1971, started a band: The Neon Boys. Miller borrowed a surname from French symbolist poet Paul Verlaine, while Meyers became Richard Hell.

It was a vulnerable and conflicted friendship, intense and competitive. Hell the rebellious hotwire, Verlaine a study in cool reserve. “Tom and Richard were very much a yin/yang couple,” says Kaye. “I think they enhanced parts of each other’s personality that needed developing, almost like a mirror where you see what you want to be and don’t want to be. They did a poetry magazine together, where they constructed a persona – a fictional female poet and ex-prostitute from Hoboken called Theresa Stern – by aligning each of their faces.”

Meanwhile, Verlaine’s guitar-playing was growing ever more distinctive and ambitious. The Byrds, Dylan and the Stones had been ‘60s touchstones, but he drew greater inspiration from the free jazz adventures of Albert Ayler, Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane.

As the Neon Boys floundered, Verlaine started gigging solo around town. Richard Lloyd, then looking to join a band, caught him at Greenwich Village cabaret club Reno Sweeney in October 1973. “The first thing I remember was how put out he was by having to carry his own guitar and amp through the door,” Lloyd recalls. “But when he started playing he was quite something. I saw that he had the thing – the it – that I was hoping for in another person. I thought I could augment that.”

Lloyd would become part of The Neon Boys, who swiftly renamed themselves Television. They made their live debut – with Hell on bass and another old Delaware ally, drummer Billy Ficca – at the Townhouse Theatre on 2 March 1974.

Their slow ascent to greatness was initially honed over a weekly residency at CBGB that spring and support slots for Patti Smith at Max’s Kansas City. Smith and Kaye saw Television for the first time at CBGB, on Easter Sunday 1974. “Tom and Richard stood on opposite sides of the stage and Richard Lloyd was in the middle,” Kaye recalls. “Early Television was definitely bipolar in the truest sense. There was Richard Hell, kind of deconstructing music and building it back up, while Tom was almost a musical intellectual. He had so many free jazz roots. He liked garage rock. And as we got to know him, we got a real sense of his expanse as a guitar player. He makes each note mean something. He was always interested in how to express himself through the guitar, a very complex person.”

Jay Dee Daugherty, then drummer with The Mumps but soon to join the Patti Smith Group, attended the Max’s run. “Television were raw, exciting, uneven and teetering on the edge of chaos,” he remembers. “Tom’s originality as a songwriter and guitarist was so refreshing. You knew you were hearing something that certainly had antecedents, but had been reassembled in a way you would never have thought of. I was entranced by them.”

Daughtery would go on to engineer Verlaine’s epic “Little Johnny Jewel”, Television’s debut single, in August 1975. By then, Hell was out of the band, replaced by the more reliably adept Fred Smith. Television’s music may have been the result of a simpatico ensemble, but Verlaine was clearly in charge. The band’s ‘TV’ initials were no accident.

Hell – who politely declined to contribute to this feature, feeling he’d said enough about his testy relationship with Verlaine in his memoir I Dreamed I Was A Very Clean Tramp – was the first to fall foul of his dominant stewardship. “This town wasn’t big enough for the both of them,” notes Kaye. “And each of them had a very specific vision they wanted to pursue.”

Warranted or not, the popular image of Verlaine tended to be that of a slightly sour contrarian. Lloyd was quite happy for Verlaine to lead Television in the beginning. “But then he began to say no to gigs, on top of everything else,” he says. “He was very much the musical arbitrator of what we would or wouldn’t do.”

According to Lloyd, Verlaine turned down Malcolm McLaren’s pitch, pre-Sex Pistols, to manage Television. The same went for Tommy Mottola. And David Bowie’s offer to produce them. Marquee Moon was instead an object lesson in artistic control and endless patience. As one of the last original CBGB bands to record, Television were governed by Verlaine’s idea of optimal timing.

“Tom wouldn’t let anybody in that told him what to do,” Lloyd adds. “Tom had a twin brother who was into drugs and perished in the ‘80s. He never mentioned him. I think they’d been fighting in the womb for space. He wasn’t very fond of other people, especially musicians. Tom didn’t have a social life that could be seen. He would never go to CBGB’s, whereas I was always there. Smoking cigarettes and drinking coffee was his thing.”

While it’s evident that he and Lloyd didn’t get along, others have more agreeable recollections of Verlaine. “Television and the Patti Smith Group were a kind of brother and sister band,” Kaye explains. “Tom was very much a part of Horses, he played some beautiful solos on ‘Break It Up’ and ‘Elegie’. Tom and Patti had a pas de deux, as they say. They had a shared affection for flying saucers and detective stories and arcane films. I think they both inspired each other.”

Then there’s Verlaine’s sense of humour, an attribute not always apparent to those on the outside. “Besides being one of the sharpest cats I’ve ever met, Tom can be one of the funniest, laugh-out-loud people you can imagine,” insists Daugherty, who became a regular in Verlaine’s post-Television line-up. “His sense of the absurd is acute, sometimes genius and occasionally unrelenting. I’ve seen him stay in character of invented personae for extended stretches of time.”

Kaye cites one tour with Patti Smith in which he and Verlaine conversed in the raspy tones of Froggy The Gremlin, a character from ‘50s TV kids show Andy’s Gang, for an entire fortnight. “It was really kind of subversive children’s humour,” he says. “I think a lot of times Tom’s lyrics are really humorous too, though you have to go through a veil of imagery to find them.”

On the business front, Television’s split, post-Adventure, came as no surprise. Verlaine phoned Lloyd to tell him he was leaving the band. Lloyd replied that he’d been thinking about quitting too. Television ended in the summer of 1978. Verlaine wasted no time in assembling a studio band to record his first solo album.

The players on 1979’s Tom Verlaine included Daugherty, Fred Smith, B-52’s guitarist Ricky Wilson and John Cale/Patti Smith keyboardist Bruce Brody. “He was very charismatic in the studio, very calm,” Brody recalls. “You could tell he knew what he wanted, but also gave you the freedom to play your own thing. He wasn’t dictatorial in the slightest.”

Charcterised by devilish guitar, melodic verve and oblique wordplay, the album set the tone for the rest of Verlaine’s solo career. David Bowie acknowledged its influence almost immediately, recording “Kingdom Come” for 1980’s Scary Monsters. Bowie’s great hope, he said, was that Verlaine might attract a bigger audience.

The chance came pretty quickly. Invited to appear on the Scary Monsters sessions in New York, Verlaine instead engaged in the kind of wilful perfectionism that might otherwise be construed as self-sabotage. According to producer Tony Visconti, Verlaine spent the entire session trying out around 30 different guitar amps, repeating the same musical phrase on each in search of the ideal sound in his head. There was so little time left for recording that his contribution, if any, remains unheard. Nor did he return the following day.

Verlaine instead pressed on alone. Several of the same musicians from his debut came back for 1981’s Dreamtime (arguably Verlaine’s finest solo album), alongside newcomers like guitarist Ritchie Fliegler, another John Cale stalwart. “That was a very positive work environment,” asserts Fleigler. “And it was much more collaborative than people might imagine. We were all just sitting around playing, working out Tom’s songs, putting flesh onto bones. There was nothing oppressive or difficult about it. And it’s such a great-sounding record.”

Tom Verlaine is evidently no social animal. Yet for someone who seems to prefer a certain degree of distance, he’s not averse to the odd collaboration. And the less likely the better. In 1984 he produced “Swallows In The Rain” for obscure Glasgow quintet, Friends Again. The same year saw Verlaine repeat the favour on In Evil Hour, from Liverpool indie types The Room.

“He wouldn’t get up until midday, then he’d have a block of ice cream for breakfast,” recalls The Room’s singer Dave Jackson. “At the time, Becky [Stringer, bassist] and I were both reading Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler and James M. Cain, writers that he was really into. So we kind of bonded over that. And I liked his sarcastic humour.”

Verlaine even relocated to the UK for a time. “We ended up supporting him at The Electric Ballroom and The Hacienda,” continues Jackson. “He wasn’t sure about us doing those gigs, because he said he normally doesn’t get on with support bands and didn’t want to fall out with us. Then he came to watch us at The Marquee and told us off for being too loud! I remember him being quite rude about other bands. He heard Lloyd Cole’s version of ‘Glory’ and said it sounded like it was being played by a Soviet military band.”

Love And Money’s James Grant recounts a similar experience in early 1987, when he and his bandmates backed Verlaine on Channel 4’s The Tube. “He was pretty laconic on the whole, but we would have a laugh,” says Grant, whose Verlaine connection began with the aforementioned Friends Again. “In terms of other artists, I wasn’t sure what he liked, but I got to know what he didn’t. One night I’d watched a TV programme where David Byrne had bigged up Television. I told him, ‘I saw your pal David Byrne on the telly, saying nice things about you.’ Tom said: ‘HE’S. NOT. MY. PAL.’”

Grant remembers rehearsing for The Tube – where Verlaine showcased a couple of tracks from new album Flash Light, including a suitably explosive “Bomb” – at Maryhill Community Centre in Glasgow: “He played like he was about to burst into flames at any given moment. I remember watching him solo, on some bedevilled wave in those rehearsal rooms, thinking, ‘How fucking bizarre is this!’”

Grant and Jackson were just two of a number of next-generation artists indebted to the music of Verlaine and Television. His solo albums may not have been selling in huge quantities, but his cult status was enriched by the likes of REM, Echo & The Bunnymen, the Banshees and Rain Parade, all of whom covered Verlaine songs during the ‘80s.

As he moved into the next decade, it appeared as though he might finally have hit a perfect balance between the twin phases of his creative life. 1992’s Warm And Cool, a set of abstract instrumentals, coincided with Television’s return to the studio after a 14-year absence.Television was a strapping comeback, issued just as grunge and the new breed of American alt.rock were in ascendancy, as if to remind people of the band’s cultural significance.

Thrillingly too, there were live gigs: a Glastonbury set, European dates, shows in Japan, coast-to-coast treks throughout the States. Verlaine was poised for an extended run through the rest of the ‘90s. Not for the first time though, it didn’t pan out that way. Television were done with each other, again, within 12 months of reuniting. Verlaine dipped from view too. It would be several years before he returned to live performance. And much longer when it came to recording.

Jimmy Rip has known Verlaine for 40 years, having first played on 1982’s Words From The Front. The guitarist has since featured on most of his subsequent solo albums, as well as touring the world with Verlaine, either as part of Television or his solo band. Often they go out as an electric duo.

“Tom and I always ride in the same car together on tour, with me driving,” says Rip, who also heads up Jimmy Rip & The Trip. “We’ve travelled hundreds of thousands of miles together and have never done anything but laugh. I’m probably as close a friend as he’s got and I really consider Tom a brother. We have these amazing conversations, but he’s very guarded about his personal thoughts when it gets to a certain point. I’ve been as many layers down as you can get, and I know not to push it.”

Rip adds that Verlaine was initially so protective of his privacy that he used to ask to be dropped at a specific street corner in Manhattan after arriving home in the early hours. It was another eight or nine years before he allowed Rip to drive him to the building he actually lived in. “I thought it was hysterically funny,” he offers. “I didn’t get offended by it. That’s just Tom.”.

A year after Rip appeared on Songs And Other Things – one of two Verlaine albums released in 2006, alongside the all-instrumental Around, his most recent studio recordings – Lee Ranaldo recruited Verlaine for the I’m Not There project. He took his place in the Million Dollar Bashers, a supergroup that also included Wilco’s Nels Cline, Dylan bassist Tony Garnier and Ranaldo’s Sonic Youth bandmate, Steve Shelley.

“By nature, I think Tom is generally suspicious of people asking him to do things,” explains Ranaldo. “But when he saw that we were really dedicated to doing a good job because of our love for Dylan and Todd Haynes, he finally agreed.

“Getting to play dual guitars with Tom for a week was thrilling in itself,” he adds. “We were tasked with recreating the electric Dylan of ’66, but then Tom had this idea to do ‘Cold Irons Bound’, from a much later period [1997’s Time Out Of Mind]. It’s one of the greatest production performance things I’ve ever been involved with. Tom really transformed it into something of his own, slowing it right down to this wide-open song that lasted seven or eight minutes. He really had a vision for what he wanted. It was just beautiful.”

Verlaine has since made cameo appearances on albums by James Iha, Violent Femmes and longtime ally Patti Smith, but “Cold Irons Bound” marks his last truly compelling studio offering. Rip’s yearly appeals to complete the ‘lost’ Television album continue to fall on stony ground. Making records isn’t something that appears to excite Verlaine right now. His last stage performance, meanwhile, came in May 2019, with Television in Chicago.

He hasn’t disappeared altogether though. “I know that Tom’s playing guitar and always working on ideas,” reveals bassist and producer Patrick Derivaz, who debuted with Verlaine on 1992’s Warm And Cool. “I meet him every couple of weeks and it’s not always about just playing music. We’ll have lunch together. He likes Indian and Middle Eastern food. Or sometimes we’ll have a Mexican. We’ll talk about books, film, music, what’s happening in the world, all the craziness with Covid. It can be anything. In fact, he sent me an email just this morning.”

Ranaldo notes that his partner, photographer and artist Leah Singer, regularly runs into Verlaine on a street corner in Chelsea, close to his home. “Tom’s out on the street smoking, always in the exact same spot, which is kind of funny,” he says. “And you’ll see him around town, combing the bookstores.”

So much for day-to-day life. But what about work? Jimmy Rip has a theory about Verlaine’s prolonged sabbatical. “In my experience, Tom’s not the most generous person with emotions,” says Rip. “And maybe that filters down to why there’s such a lack of output. I think he keeps all that very, very close to him. He’s always been careful to look after the aesthetic of Television and doesn’t feel the pressure to make another record. Being on stage and making records is not a business to him. It’s really his life.”