Following yesterday’s sad news about Ginger Baker’s passing, here’s the unexpurgated version of our 2013 interview with the great drummer, conducted by Nick Hasted at his home in Kent. This interview took place around the release of Jay Bulger’s documentary, Beware Of Mr Baker.

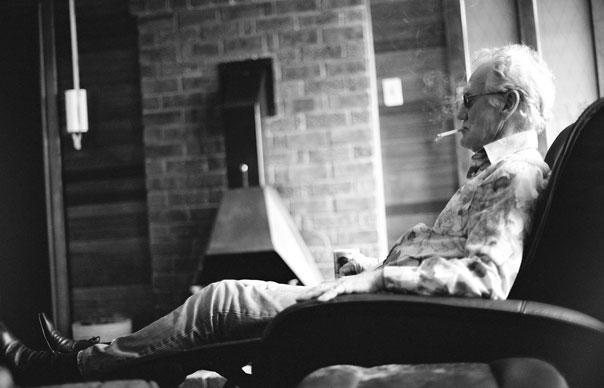

The doorbell rings at a modest house on the outskirts of Canterbury, where Ginger Baker has lived since he lost his ranch in South Africa two years ago, his fortune exhausted by his passion for breeding polo ponies. Five minutes later, the front door is grudgingly cracked open. Inside, the notoriously cantankerous Baker, white-haired and wearing a rumpled grey sweater and trousers, lays on his sofa, feet up, watching women’s tennis on TV. He brusquely shakes hands but doesn’t say hello or, later, goodbye. Photos of the beloved polo ponies he had to leave behind in South Africa stare down from the wall above the TV, which he reluctantly turns down for the business of an interview. We are here essentially to talk about Beware Of Mr Baker, a documentary by filmmaker Jay Bulger that traces the drummer’s colourful life and career, from south London to South Africa and beyond. But in fact, Baker talks about his time with Fela Kuti, Cream and his earliest days as a jazz drummer in Soho – as well as being shot at, bribed and fighting with former bandmates.

What did you think of the film?

The film was made at a very bad time for me, really. Everything was unravelling and coming apart. I’ve seen it once. Some of it is good. And some of it is awful. Where he got Art Blakey and Elvin Jones and Max [Roach] on there, that was the highlights of my career, was meeting with them and playing with them. The film is Jay Bulger’s interpretation, really. Because he kept pushing to do things which were just not part of my life. That’s when I got more and more angry. Probably that’s what makes the film.

The most interesting part of the film is your six years in Lagos in the early ‘70s. How did you end up there?

Originally I went to Ghana. And when I was in Ghana it was during the civil war in Nigeria. But all the music I kept hearing was on Radio Nigeria, so I decided to go there. They wouldn’t give me a visa ‘cause there’s a war going on, so I sent two people I knew in Nigeria a telegram saying, “I’m coming,” and the army met me at the airport and said, “Welcome to Nigeria.” It was really quite amazing.

So you were following the music into a war zone?

Well, the war was still going on there, yeah.

Was it quite a culture shock to go from Harrow to Lagos?

No. I enjoyed it. The Nigerians were really good people. I’d known Fela 10 years before that in London, and his band was just packing everywhere in Nigeria. It was one of the great things when Tony Allen his drummer was sick and I did some gigs with him in Nigeria.

When you were living in Lagos, did you go to the Shrine a lot?

Yeah, of course, and every time I had to play “Gentleman” with the band, because that was his favourite number with me and them for some reason.

When you were playing hard in that place, would you get out of your body a bit?

I’ve never played the drums hard. You shouldn’t expel great effort. I mean there was a period when Cream got very loud that I had to play loud just to hear what I was saying.

Were you drumming any differently when you were out there, playing Afrobeat with Tony and the rest of Africa 70?

No. I’ve never played any differently, wherever I play. I play as I feel, or do what I hear.

Obviously politics was very important to Fela at the time. Did you pay much attention to that?

Yeah, I was a member of the Kalakuta party. I was one of the Select Committee. The only white man there [chuckles]. There were two of us that were moderates. When we left, the radical sector took over more, and they got a little bit over the top, I thought. Because Nigeria’s a very tough place, and I was involved in the thing when he sued the police and won the case, it was quite amusing. But then he decided to attack the army. And the army were ruling the country. [Head of State General] Obasanjo was responsible for all the bad things that happened to Fela, including the death of his Mum. He went a little bit over the top. Like there was a political rally over there where over 250,000 people attended at this big football stadium they built for the All-Africa Games, everybody smoking dope. The government were severely worried about Fela, because he was so popular. If he’d have played his cards right, he could well have become the President of Nigeria. We called him the Black President. Unfortunately, he just did some things which really he shouldn’t have done. I was in a very strange position, because I was playing polo, and mixing with all the heads of government [chuckles], so I got both sides of the story, as it were. It’s a tough place, and people with power there are ruthless and very dangerous.

Did you ever feel in any danger there?

Ha-ha, God. Yeah, lots of times, ha-ha-ha. Good thing is, the Nigerian police are not very good shots. And the army. I’ve been shot at by both forces at different times. My driving ability got me out of there…

Why did you end up leaving?

Well that was because EMI destroyed my studio in Lagos, because they considered me a threat to their position in the music business. They told me to my face they were going to screw me, and promptly did so. And so in the end I lost all my money. I lost over £340,000 in 1975. Which is a lot in today’s money. It was all my Cream money. And then I just happened to meet the Gurwitz brothers, and their manager, Bill Fehilly, who was a really cool guy. And they sort of bribed me to leave Nigeria. Well I didn’t have much left there. And I did that thing [the Baker Gurwitz Army].

It was brave to have just followed the music, and vanished from the Western music scene for six years.

I’ve done that several times. After that, I went to Italy, and then to America. And then to South Africa. I was out of this country for 31 years.