Checking emails over the weekend, I was more than passingly alarmed when I got a message from a friend asking if I’d heard the news about Lou Reed. This sounded somewhat ominous. Lou has looked decidedly frail at recent London shows and he is after all 71 and despite being sober for many years has not always led the kind of lifestyle that could be described as wholly healthy. For a long time, he seemed alongside Keith Richards the rock star most likely to become a casualty of what might euphemistically be described as reckless living. Could the excesses of his past finally have caught up with him? As it turned out, the news wasn’t as awful as I had momentarily feared. He’d apparently had a life-saving liver transplant. This was clearly a pretty serious business, but it was greatly reassuring that the cantankerous old buzzard was on his way to a full recovery. What a relief! The world without Lou didn’t really bear thinking about, frankly. I’ve been listening to his music almost since I’ve been listening to music and not much I’ve heard over the years has compared even vaguely to the impact on my adolescence of The Velvet Underground, who when I first heard them at 15 seemed as far out as you could get. Later, I would have several more generally raucous encounters with Lou, who took some kind of unlikely shine to me when I interviewed him for what used to be Melody Maker in early 1977 and shortly thereafter took me on tour with him, a lively week in northern Europe from which I sometimes think I have not quite recovered. There were several similarly memorable encounters to follow, including a trip to New York just after the release of Street Hassle, in 1978, where the picture above was taken . We were staying at the Essex House, on Central Park, where we met for breakfast, decided we weren’t hungry and went to the bar for a drink instead, Lou ordering an Irish coffee. “Sure,” the barman says. “I’ll just send out for an Irishman to make it.” Lou rolls his eyes, not a good sign. “Listen,” he says then, enough edge in his voice to make you flinch. “If I’d wanted a fucking comedian, I’d have called room service. Just fix the fucking drink. Make it a double.” “Whaddya want?” the barman asks. “You want two Irish coffees?” “No. I want a double shot,” Lou tells him. “And don’t miss the fucking glass, OK? I don’t want to have to lick my drink off the bar.” Lou’s surliness, as ever, knows no bounds and he is soon unhappy in the bar, suggests we go up to his room before we are too drunk to move. When we get there, I can’t believe what I’m looking at. It appears to have been ransacked or bombed, like something you’d see in newsreels from a war zone, refugees huddled in a corner, gaunt-eyed under a single light bulb, surrounded by the rubble their lives have become. Lou walks in and indifferent to the outrageous clutter slumps in a chair, surrounded by amplifiers, guitars, flight cases, suitcases, synthesisers, video games, stacks of cassettes, trailing miles of wires and cables. There are clothes everywhere, glass underfoot. Trays of drinks are stacked on the floor next to the door, a pyramid of empties, evidence perhaps of long nights here, fuelled by alcohol and whatever else it is that Lou currently has a taste for. I fling half-a-ton of debris off the bed, and collapse upon it. Lou, meanwhile, is keen to show off his new Roland Guitar Synthesiser, which he now switches on and starts strumming. “This is the greatest guitar ever built by human people,” he starts to babble. “It makes every other guitar look tragic. It’s the invention of the age.” He presses something on the guitar and out comes a squall of noise. “Isn’t that impressive? Am I not The King Of Flash? No? Then fuck you. “ Lou now begins to play the classic intro to the Velvets’ “Sweet Jane” and presses something else on the guitar that makes the riff repeat itself. Now, of course, it won’t stop, which makes Lou mad. He starts flicking switches, pushing buttons, swearing under his breath. He gives the guitar a smack with the flat of his hand, and suddenly it starts howling, which makes us both jump. Now, he’s looking for somewhere to turn the infernal thing off at the mains, but can’t find a plug. He grabs the Medusan tangle of wires and leads at his feet, tugs hard, pulling a lamp off a table on the other side of the room. “Motherfucker,” Lou snarls, giving the recalcitrant contraption a fearful glare and leaning it on the wall behind him, where for the next few hours it repeats the same chords over and over and over. There’s a knock at the door not long after this, which turns out to be room service with two bottles of whiskey I can’t remember anyone ordering. And now this is Lou pouring extremely large measures of the whiskey into a couple of glasses he’s found under the bed. We seem to have been here for a very long time, Lou talking non-stop and me trying to make sense of his often tidal incoherence. Lou lights a Marlboro, takes a deep drag. He’s been chain-smoking for most of the time he’s been talking and so the room looks like it’s been tear-gassed, a curtain of smoke hanging in the air between us thick enough to choke a dog. “I am of a mood these days,” Lou is telling me, although don’t ask me why, “that tells me that I’m a right-wing fascist liberal. I cover all bases. I’m very legitimate on a number of levels. That’s why I’m still here. That’s why I still matter. I’m the only honest commodity around. I always was. I mean, even when I was an asshole, I was an asshole on my own terms.” I ask him when in his career he was the biggest asshole. “Don’t push it,” he says. I’m only using your own words. “Use your own fucking words,” he says sharply, and I don’t know where any of this is going. ”The thing is, I was never an asshole. I think an asshole is somebody who wastes time. It’s not a question of good or bad. The work I’ve done over the last four or five years, whatever anyone thinks of it, is by definition the best I could have done at the time. I did the best I could, because I always do. No doubt about it. If someone doesn’t like it or thinks I could have done better, fuck them. I don’t need some simple-minded savage telling me when I’m good or bad. I know when I’m good or bad. And I’m never bad. Sometimes, I don’t bother, but that’s because for a while I just didn’t care. Even then, I always assumed I was great. I never doubted it. Other people’s opinions of me don’t matter. I know my opinion is the one that’s right. The only mistake I’ve made over the years was listening to other people. ‘Hey, Lou,’ I finally said, ‘can’t you understand that you’re right and they’re wrong?’ That’s when I stopped listening to other people.” What makes you convinced you’re always so right and everyone else so wrong? “Because I can do it right in front of you, just like that,” he says, snapping his fingers for emphasis and almost falling off his chair. “And it’s not very hard for me, although apparently it is for other people. Even now, I don’t think there’s anyone in rock’n’roll who’s writing lyrics that mean anything, other than me. You can listen to me and actually hear a voice. These other people are morons. They really are. I’ve only known a few people I thought were any good. Delmore Schwarz. Andy. One thing Andy taught me,” he says, the conversation going off in what appears another new direction, “was that if you start something, finish it. And I started something when we started The Velvet Underground and put out ’Heroin’. And then I left it for two years. But I knew I hadn’t finished what I’d started and it didn’t feel good. But I didn’t care at the time. I thought, ’Why should I go back? Why should I even bother to finish what I started? Does anyone deserve it? Look at all those people out there. Will they even understand, most of them, what I’m doing? No, of course they won’t.’ But in the end, lo and behold, I returned. “I decided to come back and finish it. What else was I going do? Walk away and leave it? Uh-uh. I wasn’t prepared to have all the people who’d ever had any faith in me think I’d turned out to be a total sham. Fuck that. People think on many levels that I’m a vicious and conniving this and that, who doesn’t do the right thing, who’s self-destructive, who can’t be trusted, that I don’t give a shit. But I do. Always have done. And the main thing is that it’s always Lou Reed. And he’s always doing it. And sometimes it’s not what people want, because whatever else it might be, it’s always real. That’s the thing. And a lot of people are frightened of that. They’re actually frightened of people like me, because we’re too fucking real for them. That’s what they’re really afraid of. And they should be, too. “Because some of us really aren’t kidding, you know? And we just keep going. And they can’t stop us, man.”

Checking emails over the weekend, I was more than passingly alarmed when I got a message from a friend asking if I’d heard the news about Lou Reed. This sounded somewhat ominous. Lou has looked decidedly frail at recent London shows and he is after all 71 and despite being sober for many years has not always led the kind of lifestyle that could be described as wholly healthy. For a long time, he seemed alongside Keith Richards the rock star most likely to become a casualty of what might euphemistically be described as reckless living. Could the excesses of his past finally have caught up with him?

As it turned out, the news wasn’t as awful as I had momentarily feared. He’d apparently had a life-saving liver transplant. This was clearly a pretty serious business, but it was greatly reassuring that the cantankerous old buzzard was on his way to a full recovery. What a relief! The world without Lou didn’t really bear thinking about, frankly. I’ve been listening to his music almost since I’ve been listening to music and not much I’ve heard over the years has compared even vaguely to the impact on my adolescence of The Velvet Underground, who when I first heard them at 15 seemed as far out as you could get.

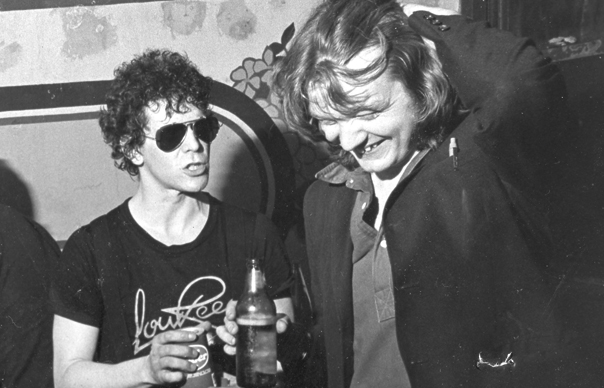

Later, I would have several more generally raucous encounters with Lou, who took some kind of unlikely shine to me when I interviewed him for what used to be Melody Maker in early 1977 and shortly thereafter took me on tour with him, a lively week in northern Europe from which I sometimes think I have not quite recovered. There were several similarly memorable encounters to follow, including a trip to New York just after the release of Street Hassle, in 1978, where the picture above was taken .

We were staying at the Essex House, on Central Park, where we met for breakfast, decided we weren’t hungry and went to the bar for a drink instead, Lou ordering an Irish coffee.

“Sure,” the barman says. “I’ll just send out for an Irishman to make it.”

Lou rolls his eyes, not a good sign.

“Listen,” he says then, enough edge in his voice to make you flinch. “If I’d wanted a fucking comedian, I’d have called room service. Just fix the fucking drink. Make it a double.”

“Whaddya want?” the barman asks. “You want two Irish coffees?”

“No. I want a double shot,” Lou tells him. “And don’t miss the fucking glass, OK? I don’t want to have to lick my drink off the bar.”

Lou’s surliness, as ever, knows no bounds and he is soon unhappy in the bar, suggests we go up to his room before we are too drunk to move. When we get there, I can’t believe what I’m looking at. It appears to have been ransacked or bombed, like something you’d see in newsreels from a war zone, refugees huddled in a corner, gaunt-eyed under a single light bulb, surrounded by the rubble their lives have become.

Lou walks in and indifferent to the outrageous clutter slumps in a chair, surrounded by amplifiers, guitars, flight cases, suitcases, synthesisers, video games, stacks of cassettes, trailing miles of wires and cables. There are clothes everywhere, glass underfoot. Trays of drinks are stacked on the floor next to the door, a pyramid of empties, evidence perhaps of long nights here, fuelled by alcohol and whatever else it is that Lou currently has a taste for. I fling half-a-ton of debris off the bed, and collapse upon it. Lou, meanwhile, is keen to show off his new Roland Guitar Synthesiser, which he now switches on and starts strumming.

“This is the greatest guitar ever built by human people,” he starts to babble. “It makes every other guitar look tragic. It’s the invention of the age.”

He presses something on the guitar and out comes a squall of noise. “Isn’t that impressive? Am I not The King Of Flash? No? Then fuck you. “

Lou now begins to play the classic intro to the Velvets’ “Sweet Jane” and presses something else on the guitar that makes the riff repeat itself. Now, of course, it won’t stop, which makes Lou mad. He starts flicking switches, pushing buttons, swearing under his breath. He gives the guitar a smack with the flat of his hand, and suddenly it starts howling, which makes us both jump. Now, he’s looking for somewhere to turn the infernal thing off at the mains, but can’t find a plug. He grabs the Medusan tangle of wires and leads at his feet, tugs hard, pulling a lamp off a table on the other side of the room.

“Motherfucker,” Lou snarls, giving the recalcitrant contraption a fearful glare and leaning it on the wall behind him, where for the next few hours it repeats the same chords over and over and over.

There’s a knock at the door not long after this, which turns out to be room service with two bottles of whiskey I can’t remember anyone ordering. And now this is Lou pouring extremely large measures of the whiskey into a couple of glasses he’s found under the bed. We seem to have been here for a very long time, Lou talking non-stop and me trying to make sense of his often tidal incoherence. Lou lights a Marlboro, takes a deep drag. He’s been chain-smoking for most of the time he’s been talking and so the room looks like it’s been tear-gassed, a curtain of smoke hanging in the air between us thick enough to choke a dog.

“I am of a mood these days,” Lou is telling me, although don’t ask me why, “that tells me that I’m a right-wing fascist liberal. I cover all bases. I’m very legitimate on a number of levels. That’s why I’m still here. That’s why I still matter. I’m the only honest commodity around. I always was. I mean, even when I was an asshole, I was an asshole on my own terms.”

I ask him when in his career he was the biggest asshole.

“Don’t push it,” he says.

I’m only using your own words.

“Use your own fucking words,” he says sharply, and I don’t know where any of this is going. ”The thing is, I was never an asshole. I think an asshole is somebody who wastes time. It’s not a question of good or bad. The work I’ve done over the last four or five years, whatever anyone thinks of it, is by definition the best I could have done at the time. I did the best I could, because I always do. No doubt about it. If someone doesn’t like it or thinks I could have done better, fuck them. I don’t need some simple-minded savage telling me when I’m good or bad. I know when I’m good or bad. And I’m never bad. Sometimes, I don’t bother, but that’s because for a while I just didn’t care. Even then, I always assumed I was great. I never doubted it. Other people’s opinions of me don’t matter. I know my opinion is the one that’s right. The only mistake I’ve made over the years was listening to other people. ‘Hey, Lou,’ I finally said, ‘can’t you understand that you’re right and they’re wrong?’ That’s when I stopped listening to other people.”

What makes you convinced you’re always so right and everyone else so wrong?

“Because I can do it right in front of you, just like that,” he says, snapping his fingers for emphasis and almost falling off his chair. “And it’s not very hard for me, although apparently it is for other people. Even now, I don’t think there’s anyone in rock’n’roll who’s writing lyrics that mean anything, other than me. You can listen to me and actually hear a voice. These other people are morons. They really are. I’ve only known a few people I thought were any good. Delmore Schwarz. Andy. One thing Andy taught me,” he says, the conversation going off in what appears another new direction, “was that if you start something, finish it. And I started something when we started The Velvet Underground and put out ’Heroin’. And then I left it for two years. But I knew I hadn’t finished what I’d started and it didn’t feel good. But I didn’t care at the time. I thought, ’Why should I go back? Why should I even bother to finish what I started? Does anyone deserve it? Look at all those people out there. Will they even understand, most of them, what I’m doing? No, of course they won’t.’ But in the end, lo and behold, I returned.

“I decided to come back and finish it. What else was I going do? Walk away and leave it? Uh-uh. I wasn’t prepared to have all the people who’d ever had any faith in me think I’d turned out to be a total sham. Fuck that. People think on many levels that I’m a vicious and conniving this and that, who doesn’t do the right thing, who’s self-destructive, who can’t be trusted, that I don’t give a shit. But I do. Always have done. And the main thing is that it’s always Lou Reed. And he’s always doing it. And sometimes it’s not what people want, because whatever else it might be, it’s always real. That’s the thing. And a lot of people are frightened of that. They’re actually frightened of people like me, because we’re too fucking real for them. That’s what they’re really afraid of. And they should be, too.

“Because some of us really aren’t kidding, you know? And we just keep going. And they can’t stop us, man.”