From The Clash to Public Enemy, from Thin Lizzy to the Manic Street Preachers, there has always been a strain of rock’n’roll mythology that has fostered the metaphor of the rock band as military comrades – brothers in arms, outlaws, renegades, hunkering down behind enemy lines as they deliver volley after volley of sonic terrorism. Tinariwen – the Tuareg heavy rock outfit from Mali – seemed to be the first band that actually brought this metaphor to life. They spent their formative years in the early 1980s training in Libya as military insurgents under the auspices of Colonel Gaddafi, who saw the Tuareg as useful allies in his quest for regional supremacy.

In the years since the Libyan dictator’s downfall, things have got extremely complicated for the traditionally nomadic Tuareg people. Spread out, like the Kurds, among several countries that are hostile to them – Mali, Niger, Libya, Algeria, Burkina Faso, even part of Nigeria – they have fallen victim to the power vacuums caused by the Arab Spring.

In Tinariwen’s home nation of Mali, it has resulted in an ugly three-way civil war. The separatist Tuareg political and military organisation that Tinariwen are identified with, the National Movement for the Liberation of Awazad (or the MNLA, to use its French acronym) are fighting regional battles with Al Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), while both organisations are also fighting against a government in Bamako who are supported by the French army. To complicate things further, some Tuareg have joined government forces; other factions in the (usually secular) MNLA have allied themselves with Islamists who want to violently impose Sharia law on the region, like Iyad Ag Ghali’s Ansar Dine.

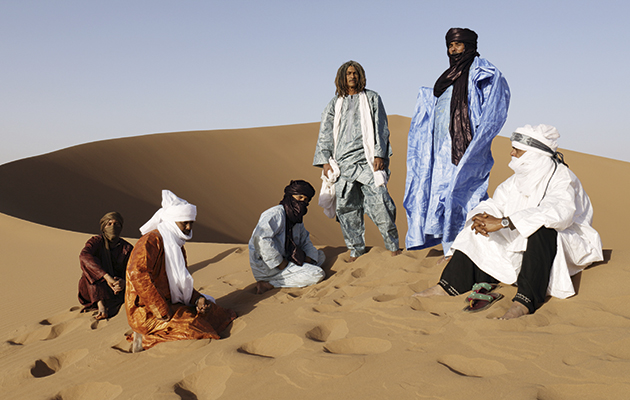

Many Tuareg have fled Mali for refugee camps. Tinariwen themselves have been in a state of flux, living on the Mali/Algeria border and recording this album in France, Morocco and California. They have frequently been targeted by Islamists who are hostile to musicians: their guitarist Abdallah Ag Lamida, was captured by fundamentalists for several months before being released.

It’s a situation that Tinariwen cannot help but address on their latest album, Elwan, which translates – in the Tamashek language in which they sing – as “the elephants”. The lyrics of “Ténére Taqqal” (“What has become of the desert”) are the most poetic and the most politically charged on the album. “The desert has become an upland of thorns/Where elephants fight each other/Crushing tender grass underfoot,” it begins, over a spidery guitar drone, a wobbly, Jaco Pastorius-style bassline and a delightfully sluggish 12/8 rhythm. Here, the elephants of the album title are the rampaging enemy, with the gazelles and birds the vanquished commoners. “The strongest impose their will/And leave the weakest behind”.

To a great extent, all Tinariwen songs have the same roots. Most are harmonically simple compositions, in a minor key, where several guitarists create a pleasing mesh of arpeggios on electric guitars. Over a clatter of complex polyrhythms, a chorus of male vocalists growl, miserably and melancholically, with the occasional frenzied “whoop” coming in after the second chorus. But, just as there’s something wrong with Motörhead playing with a symphony orchestra, or Black Sabbath doing a disco single, there’s no need for Tinariwen to deviate from this template too much, although there is development of the subtle variety. Bassist Eyadou Ag Leche provides a grinding, propulsive underscore to tracks like “Sastanaqqam” (“I Question You”, a fearsomely funky track by Abdallah Ag Alhousseyni, outlining the love-hate relationship with the desert), or “Imidiwàn n-àkall-in” (“Friends From My Own Land”, Ibrahim Ag Alhabib’s one-chord groove that mourns how “My own people have abandoned their ancestral ways/All that’s left is a groaning land/Full of old people and children”).

On the Ry Cooder-ish blues of “Ittus” (“Our goal”), written and sung by one of the new boys, Alhassane Ag Touhami, the politics are unusually bald. “I ask you, what is our goal/It is the unity of our nation/and to carry our standard high”. Here it’s an advantage to not understand the lyrics: what translates as a dry resolution from a party political conference takes on a musical power and resonance. Elsewhere, the militancy has been replaced by a slow-burning, brooding sadness. Even without reading the translations, songs like the haunted “Fog Edaghan” (‘On the mountain tops’) or the desolate, Fleetwood Mac-style blues of “Nizzagh Ijbal” (‘I live in the mountains’) that speak of loneliness; of the yawning desert of the heart, the empty land of the mind.

Tinariwen might have emerged from a heavily matriarchal Tuareg society and acknowledge inspiration from many female musicians – including the Tartit singer Fadimata “Disco” Walett Oumar – but their brand of combat rock doesn’t usually mention women at all. That’s changed a lot on Elwat. On “Talyat” (“Girl”), Abdallah Ag Alhousseyni sings a simple, lovelorn lyric for a “light-skinned girl/with blossoming face/coming out of her tent/dressed in a robe I know well”. “Assawt” translates as “The Voice Of Tamasheq Women” and again, it’s a light piece of folk-funk that reads like a piece of Soviet feminism. “That’s the voice of the Tamashek women/Searching for their freedom,” sings Abdallah. “Those are the thoughts of the old women/living in a Sahara devoid of water… my wish is for it to stop being subservient”.

Just as their last album, 2014’s Emmaar, featured guest slots from the likes of Josh Klinghoffer and Saul Williams, the tracks here recorded at the Joshua Tree in California feature several American fans. Matt Sweeney, Kurt Vile and Alain Johannes add to the tangle of guitars on tracks like “Tiwàyyen” and “Talyat”, while Mark Lanegan lends his distinctive baritone to “Nànnuflày”. But it’s the haunted croak of the band’s main singers, Ibrahim and Abdallah, that are the main draw: the sound of heartbroken gangleader, the world-weary soldier, bravado replaced by tenderness. It’s a sound that suits them perfectly.

Q&A

Eyadou Ag Leche (bass)

Why is the album called The Elephants?

The elephants symbolise the plagues of our people – big corporation, terrorists, radical Islamists, corrupted states etc. Our people, the Tuareg, are fighting since the 1960s and, in 2016, the issues are the same, or even worse. But we will still fight, look for peace and humanity. We will stay standing up again and again…

How political is this album?

I don’t know if you can call our songs “political songs”. These are just songs about what we are living everyday us and our people. Everything is political and nothing is political. This is our life.

Do you see Tinariwen continuing indefinitely, like a football team – constantly replenishing itself with new members?

Tinariwen have always been a big family of musicians since almost 30 years. Founder members like Japonais, Kedou, Intiyeden, Intidao have left: founder guitarists/composers like Ibrahim and Hassan are still in the band; Abdallah came later, and now myself 15 years ago and now Sadam (of Imarhan) join the band sometimes. The power of Tinariwen has always been to have multiple personalities of composers and it make the band identity unique, I hope it will continue again and again, but who knows?

What did Mark Lanegan, Kurt Vile, Matt Sweeney et al brought to the recordings?

We meet a lot of great artists on the road, and a lot of well-known musicians love our music. So we are always open to collaboration with others because we think our music needs to travel around the world. Kurt and Matt came for a recording session in Rancho de La Luna in Joshua Tree for few days, jamming with us. We kept a lot of stuff on the album. Alain Johannes was with us during this session, and Mark Lanegan said he loves the band and wanted to record with us. Unfortunately he was sick when we were in Joshua Tree so he recorded his vocals later on!

Your music seems to getting funkier, particularly your basslines…

Ha ha, thank you! Maybe it is because I love James Brown, Fela Kuti and Jimi Hendrix. I love to dance too! So I think that’s why.

INTERVIEW: JOHN LEWIS