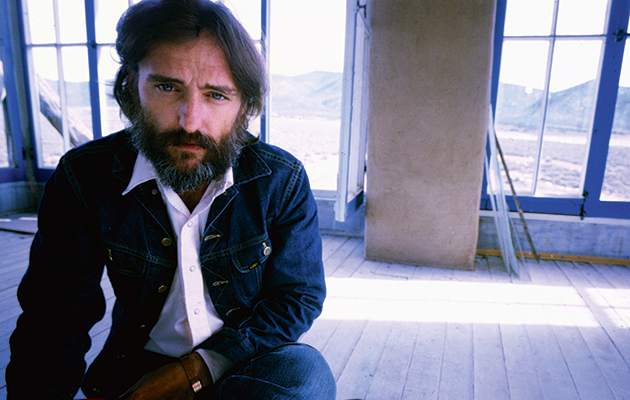

In the winter of 1970-71, the writer and actor LM “Kit” Carson visited his friend Dennis Hopper’s house outside Taos, in the desert of New Mexico. Hopper had recently returned from shooting The Last Movie in Peru’s and was busy editing the 48 hours of footage he’d brought back. After five days, Carson was convinced the process needed to be documented for posterity. Joining forces with photographer-turned-director Lawrence Schiller, the pair returned with a 16mm camera to shoot a free-form portrait of Hopper in his wild and lonely kingdom.

By turns excruciating and mesmerising, embarrassing, sordid, banal and beautiful, the resulting film has since become legend. Partly because few other director portraits find the auteur under study stripping off and strolling naked along a suburban sidewalk. And partly because, for 45 years, it has been practically impossible to see.

As part of his countercultural mission statement – and his mission to boost his revolutionary image – Hopper instructed Schiller and Carson to only distribute the film on university campuses. For decades, then, The American Dreamer existed only as scratched college prints or bleary bootlegs. But now, fuly restored, it is finally being released. The film will be available on the arthouse video-on-demand service MUBI from February 12-March 13; meanwhile, a region-free Blu-Ray/ DVD combo has been issued by Etiquette Pictures in the US.

If The American Dreamer was envisaged as a countercultural rallying cry in 1971, what lends it potency today is our retrospective knowledge of what came next. The film ostensibly captures Hopper at his height, having shaken the industry with the phenomenal success of Easy Rider and poised to make the film of his dreams.

In fact, though, it freezes him at the edge of an abyss, about to experience the career-wrecking commercial failure of The Last Movie, and enter a wilderness from which it would take a decade-and-a-half to emerge. Most striking is how, beneath his exhausted bluster and bat-shit posturing, Hopper seems to sense it coming. Early on, Schiller asks what will happen if The Last Movie doesn’t find an audience. Hopper assures him it will; then, tellingly, ruminates on Orson Welles, whom he’d recently encountered going cap-in-hand around the studios, failing to get funding.

Pressure was building on Hopper. For different reasons, the acidheads of the counterculture and the heads of Universal studio were both on his back, impatient to see his Easy Rider follow-up. Added to the weight of their expectations were his own. The Last Movie meant far more to him than Captain America. It was a movie he’d been dreaming about since the early-1960s, and a deeply personal statement about Hollywood’s destructive effects. As he started editing, though, he found it slipping out of reach. Originally scheduled for three months, it would take him over a year to complete his cut.

Meanwhile, he’d just come out of his disastrous eight-day marriage to Michelle Phillips, and was looking to sleep with every woman he could. Meanwhile again, his appetite for booze and drugs was tipping into addiction. More than filming him working on The Last Movie, Carson and Schiller film Hopper not working on it: firing rifles in the desert; offering philosophical pearls such as, “I don’t believe in reading”; and, indeed, bent double on a broken bed, baring his ass for fondling by a coterie of 30 naked young women, in a toe-curling group “sensitivity encounter.”

Alongside Orson Welles, the other phantom on Hopper’s mind is Charles Manson, whom he admits having recently visited in jail. At points, filling his compound with stoned chicks and lecturing them, it seems like Hopper, having already grown the beard, is considering picking up where Manson left off.

Then again, it pays to consider how much Hopper is playing “Dennis Hopper” here. It’s key to remember that, behind the camera, Carson had recently starred in David Holzman’s Diary, the brilliant 1967 mockumentary that debunked cinema verite and shared themes with The Last Movie: namely, how the very presence of a camera warps reality, rendering it fake. Hopper makes the very point in a scene where he takes Schiller to task over his invasive filming – a confrontation that was itself staged.

The American Dreamer isn’t simply a significant documentary about New Hollywood. With its reflexive nature, and its nagging suggestion of something that has just been missed ¬– the impending sense of “we blew it” – it’s a key movie of that wave. See it, remember the wild Dennis that was, and hope that, someday, The Last Movie itself will be released from limbo.

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.