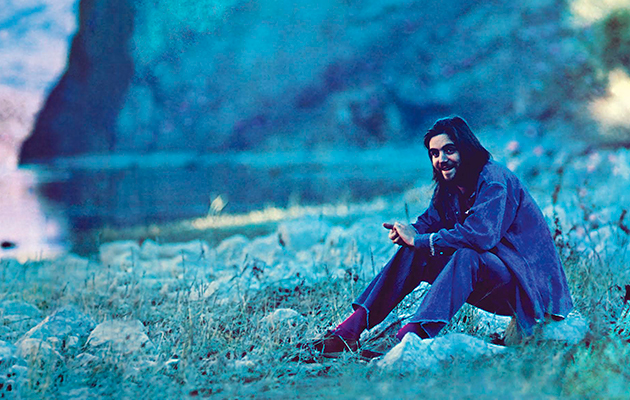

Terry Reid’s story has the itinerant singer-songwriter crossing paths with some of rock’s heaviest characters: from early days under Mickie Most’s wing, through touring with the Yardbirds and The Rolling Stones, playing a decisive hand in the formation of Led Zeppelin, to declining an offer to join Deep Purple. But what if all that was never so important; if these were, instead, merely interludes in a more personal trajectory? Listening back to Reid’s small, yet beautifully formed body of work, particularly his two stunning 1970s albums, River and Seed Of Memory, it’s pretty clear he’d never have sat comfortably with Zeppelin, who’d also offered him lead singer duties, or the Purple.

For better or worse, Reid was on his own, wholly holistic trip. A voracious listener and researcher, by the 1970s Reid had tuned into the highly advanced, political song of Brazil, from the bossa nova of Antonio Carlos Jobim through to the wild-eyed Tropicália experiments of Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil. He was also up to his knees in soul and R’n’B, and was exploring folk music from across the globe. All of this found its way into Reid’s music, a deeply syncretic and idiosyncratic take on blues, rock and soul that often found its way to popular culture thanks to the efforts of others: both The Hollies and John Mellencamp recorded his classic, “Without Expression”; ditto Cheap Trick and “Speak Now Or Forever Hold Your Piece”.

His best album, 1973’s River, has always had strong purchase within an alternate corpus of rock music, one that takes the canon at something close to its word, but allows the understated players, the characters that followed the tones rather than the mythology, their moment in the sun. River is just as elusive and gorgeous a beast now as it must have been on first listen, 43 years ago: swaying into view with the cat-scratch funk of “Dean”, coasting the shimmering, right-angled boogie of “Avenue”, and then drifting off into the acoustic bossa reveries of the album’s seductive flipside, it’s an object lesson in the power of approaching material from unexpected angles – there are things going on in River that don’t quite happen the same way anywhere else.

All of which makes The Other Side Of The River a very good thing indeed. There has long been rumour of a double-album’s worth of songs recorded during River’s sessions, and producers of this project, Pat Thomas and Matt Block, should be applauded for pulling together such strong material from the previously unreleased tapes. There are five alternate versions of songs that appear on River, which are treats in themselves, but the real core of the set is six newly available songs, all of which point outwards in different directions, another set of ways the river could have flowed.

The alternate versions are just as loose and hypnotic as those eventually released on River, but they also offer new perspectives. “Avenue” has a heavier rhythmic thunk, and the riff that instigates the groove gets driven, mercilessly, into the depths, Reid’s voice pirouetting across the gorgeous soul caress of the session’s backing vocalists, The Ikettes. He draws even more insinuated sensuality out of the bossa nova swirl of “River”; perhaps more importantly, though, hearing these songs in the context of the previously unreleased material proves just how deft a thinker and writer Reid was during the 1970s.

This Brazilian influence comes through even more strongly on The Other Side Of The River, which is unsurprising given the appearance of Brazilian music legend Gilberto Gil on the album – he was a regular at Reid’s Cambridgeshire country house, after he’d been hounded out of Brazil by the military dictatorship. “Listen With Eyes” moves with the languid shuffle of a great Carlos Jobim or Luiz Bonfà composition, proof that Reid had understood on an almost molecular level the deep structural intelligence behind the breeziness of great bossa.

There’re a good number of rockers on The Other Side Of The River, too, where Reid’s grounding in the blues comes through both in the vibrant clang of his guitar and the slack-wound grain of his voice. But the tale told by this set, ultimately, is one of relaxed experimentation, and an ability to take great, peerless players and industry mavericks – besides Gil, the group here also includes the aforementioned The Ikettes, and David Lindley of Kaleidoscope, and a good portion of the album’s sessions were produced by R’n’B legend Tom Dowd – and give them the space to mould fantastic new shapes out of Reid’s songs by finding where genres begin to buckle, and placing subtle stress on these pressure points. The end result is some of the most compelling and gorgeous rock music of its decade.

Q&A

TERRY REID

How did this whole process come about?

Warners found out that all of the tapes [for my albums] were in lockers in London. My friend Matt Block flew to London, went to the lockers, looked up and there’s a row of tapes going across of the room, all these two-inch tapes… He took them to a studio, played them, and voila, came up with 24 different pieces of material. He called me and said, “Did you know about all this?” I said, “Well, I know we did a lot!”

Do you remember recording the material?

We were in the studios for so long, for a couple of months, day to day. It’s not until you hear it that it all comes rushing back. We were doing all different kinds of things, mixing country style, R’n’B, rock’n’roll, a whole mixture of influences. We’d just keep playing things, having a lot of fun, and I got Gilberto Gil and everybody to come into the studio with me, and add little bits to what we were doing. So now there’s a whole Brazilian influence in there.

Brazilian music had some really interesting political dimensions.

The way I look at it, all music is subject to crisis, to the politics of the country of origin. I’m a really big fan of Bulgarian music. I started collecting a lot of the music from there, Romania, Yugoslavia, and when you listen to their folk music, you hear all these Turkish influences. All the conquerors that came through, they left – well, they left a mess, but they also left the influence of their own music.

INTERVIEW: JON DALE

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.