At 75, David Crosby is feeling frailer and more insignificant than ever. We should be thankful. Like Johnny Cash and Leonard Cohen – you could also throw in Rembrandt and Matisse – Crosby has found that the various urgencies and indignities of old age have precipitated a remarkable creative spurt.

Twenty years elapsed between his third solo studio album, Thousand Roads, and the fourth, 2014’s Croz. It has taken only two for the fifth to arrive, and a sixth is apparently imminent. The fact that CSN and CSNY appear to be on indefinite hiatus has no doubt also helped concentrate his energies.

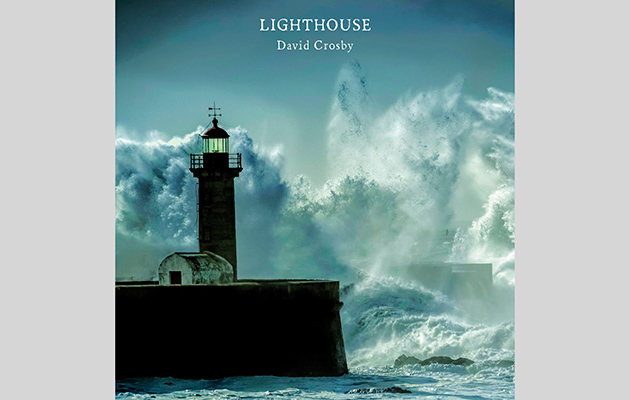

Lighthouse was composed quickly and recorded with almost indecent haste, cut in 12 days with Crosby’s new writing partner, Snarky Puppy’s Michael League. And while Croz was polished to a smooth sheen – the overall effect was one of pleasant but slightly anodyne proficiency – Lighthouse is looser, and significantly bolder. It’s a thoughtful, profound and intensely beautiful late-blossoming career highlight, as light and airy in its musical choices as it is weighty in its subject matter.

Sensibly, Crosby makes a central feature of his natural attributes. Voice and guitar are the load-bearing beams. The former, frequently layered in a stack of glorious harmonies, remains a silken wonder. His acoustic guitar playing, too, is inimitable, the exotic tunings taking the melodies on lovely, unexpected detours. Around these constants League adds painterly production touches: slithers of bass, washes of organ, solid piano chords. There are no drums. Only “The City”, which has something of the crunchy rhythmic thrust of “Cowboy Movie” from Crosby’s classic 1971 solo debut, If I Could Only Remember My Name…, features the most rudimentary time-keeping.

Lighthouse is lit up with a kind of calm intensity. Unfussy, but far from simple. Crosby has his eyes wide open, imploring us to look: at the universe, at our lives and relationships, at the world’s suffering. The outstanding “The Us Below” is not the only song which weaves together cosmic wonder and mortal dread. Aptly, the verse melody has more than a hint of Trent Reznor’s “Hurt”, memorably covered by an ailing Cash. Its central question – “Why must we be eternally alone?” – is less a cry from one human to another, and more the lament of Mankind seeking a universal soul mate.

The fragility of humanity, weighted against the small, vital connections we make, is also the theme of “Drive Out To The Desert”, which hymns the restorative qualities of our intrinsic insignificance. “If you start to feel very small/That’s a very good sign,” he sings, recounting a meditative trip to some great unpeopled place. Lighthouse is defined by a kind of vast humility, not necessarily the first characteristic one might associate with Crosby. He sounds awed by the world.

Similar ideas permeate “Things We Do For Love” and “Paint You A Picture”, but here Crosby brings them closer to home. Written for his wife Jan, the former is both lush and vaguely disquieting, as though he’s been listening to American Music Club circa Everclear, or The Blue Nile of Hats. He walks the hard road of enduring love in the grip of coming darkness. “There’s only so much time/Reaching through the fear”. “Paint You A Picture” is an elegiac self-portrait of the artist, while “What Makes It So?” – which boasts the most beautiful melody on an album stuffed with them – finds Crosby, that enduring emblem of the counter-culture, still plotting a path of individualism, scorning accepted wisdom and convenient rhetoric. “How can there only be one way?”

More urgent concerns also creep in. “Look In Their Eyes” is Crosby’s response to “the world’s forgotten citizens”, specifically the millions of Syrians displaced in the refugee crisis. Words and music deliberately jar. With its laid-back, low-key groove, it recalls JD Souther’s later work, or Tim Buckley’s sex-funk simmering on a medium heat. “Somebody Other Than You”, conversely, sounds exactly like the bald anti-war song it is, the verses sad and serpentine, the chorus quick and waspish. Homing in on the hypocrisy of warmongers who never have to fight any wars, Crosby lays into the Bush dynasty and their catastrophic legacy in Iraq: “I’m through/Watching you grow fat/Exactly how your father did before last war.”

The album ends with the gorgeous “By The Light Of Common Day”, which gives thanks to the muse while acknowledging the price paid in order to follow her. “Being happy isn’t quite enough,” sings Crosby. “Somehow I had to make it rough/Rough enough to break it.” His voice entwines with that of the track’s co-writer, Becca Stevens, on a song which possesses the hymn-like purity of Paul Simon’s “American Tune”. As he does often on Lighthouse, Crosby flirts with outright silence, as though pausing for some vital message to come through. “The spark is there all the time now/If you know how to listen to your calling.” Crosby is listening and receiving – and communicating it all rapturously.