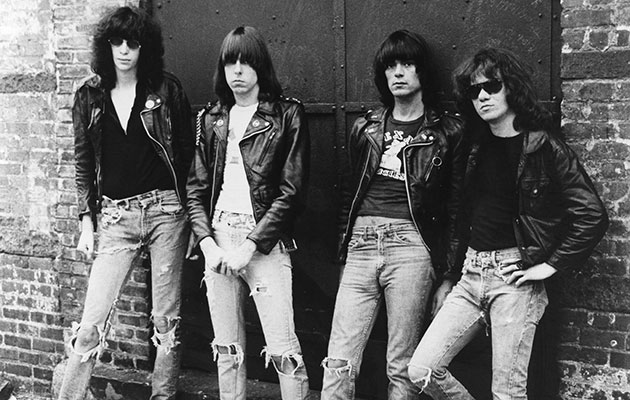

An army brat who claimed to sell Nazi paraphernalia for morphine. A delinquent who dropped TV sets off roofs. A gangling freak with OCD. And even a quietly organised music obsessive… On their 40th anniversary, Uncut pieces together the complete story of the Ramones. Or: how the four weirdest kids in Forest Hills, New York, mixed leather, pop art and the Three Stooges and accidentally revolutionised rock’n’roll – at speed. “Over 23 minutes,” says Richard Lloyd, “Led Zeppelin couldn’t match them.” Words: Peter Watts. Originally published in Uncut’s March 2014 issue (Take 202). Photo: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

________________________

Tommy Erdelyi didn’t know quite what to expect when he arrived for the Ramones’ first band practice. Guitarist John Cummings and bass player Doug Colvin had bought their instruments just the week before, meanwhile the only thing any of them knew about drummer Jeffrey Hyman was that he was a fan of The Stooges and the New York Dolls. But when they had all convened at Performance Space Studio in New York on January 28, 1974, Erdelyi was astonished to discover the existence of two brand new songs. “I was shocked because not only were they original but I’d never heard songs like this before, they were so bizarre,” remembers Erdelyi, the only surviving original Ramone. “I saw them as very artistic. One was ‘I Don’t Wanna Walk Around With You’ and the other was ‘I Don’t Wanna Get Involved With You’, which was the same song with slightly different lyrics.”

The formula the Ramones laid down that afternoon on E 20th St and Broadway served them for the rest of the decade – a busy and exciting time for the band during which they recorded five classic albums and also helped define the stylistic parameters for a new genre of music. They were called punks, but if the Ramones looked tough and acted dumb they were a hard act to pigeonhole. Birthed in New York’s CBGB’s scene, they shared a dense knowledge of popular culture and rock music that they distilled into minimalist pop poetry, reducing musical and lyrical concepts to their base elements with pop art economy. They wanted to be The Bay City Rollers, but they looked like The Velvet Underground and played faster, louder and more intensely than anybody around. It was genius but America didn’t want to know. Now, the legacy – and logo – of the Ramones is everywhere. “If the Ramones were still around they’d be playing stadiums,” says Patti Smith’s guitarist Lenny Kaye. “They became the template for punk rock – very fast eighth notes, call-and-response lyrics, deliberate dumbness, incredible propulsion.” Erdelyi sighs, “We were influential in more ways than a lot of people realise. I always thought eventually everybody would catch up with us. I didn’t realise it would take 30 years.”

________________________

Thomas Erdelyi was born in 1952 in Budapest but his family moved to America, settling in Forest Hills, a middle-class New York suburb where Erdelyi would soon bump into some like-minded souls.

“I met Johnny [Cummings] at my first day of high school in 1964,” says Erdelyi. “He was charismatic, outgoing, holding court at the lunch table. I had a feeling that one day he’d develop a cult around him.”

The pair bonded over music. Also on the scene was a lanky, gawky kid, Jeffrey Hyman, who Erdelyi met at a jam session: “I played guitar, he was drumming and didn’t say a word but I always saw him around – he was so unusual-looking you couldn’t miss him.” A year later, an army brat called Doug “Dee Dee” Colvin moved to the neighbourhood from Germany, where he told his new friends he sold Nazi paraphernalia to buy morphine. “He would tell these great stories that we later found out were kind of tall tales,” says Erdelyi.

All four loved pop music and Cummings and Erdelyi formed a garage band, Tangerine Puppets, with Cummings on bass. After they broke up in 1967, Cummings sold his guitars and drifted into dope-smoking delinquency, often in league with the impish Colvin. “Johnny was bad,” says Erdelyi. “He did things like drop TV sets off roofs. He was trying to scare people but he could have killed them. Eventually he turned it round.”

Erdelyi remained in music, playing in bands with another local boy, Monte Melnick, while also working as an engineer at the city’s Record Plant studio. “And I stayed in touch with John. I thought he should be in a band, he had such charisma. I kept encouraging him to take up music when he was working on construction sites.” Tired of seeing serious, untouchable bands play endless solos, the pair went nuts over The Stooges before discovering the New York Dolls. “They were so different,” enthuses Erdelyi. “They weren’t virtuosos but they were the most exciting thing I’d seen for years. I thought that if John could put a band together they could do something because they didn’t need to be amazing players.”

Cummings bought a $50 Mosrite guitar from Manny’s on 48th St in January 1974. “It didn’t even have a case, he had to carry it around in a shopping bag,” recalls Erdelyi. “He talked Dee Dee into getting a bass. I thought this was great, they’d put a band together and I’d be manager. We put Jeffrey on drums because he had a set and looked right. They were a trio, with Johnny on guitar and Dee Dee on bass and singing.”

The band wrote out a list of 40 possible names before agreeing on the Ramones – Dee Dee took it from Paul Ramone, a pseudonym Paul McCartney used in the early days of The Beatles. In the first of several brilliant creative decisions, the band decided to adopt Ramone as a collective surname – Cummings became Johnny Ramone, Colvin was Dee Dee Ramone and Hyman was Joey Ramone. People assumed they were brothers. “It created a sense of unity, a bond of sorts,” Joey would say. “We might have got it from the Walker Brothers, but we liked it as an idea,” admits Erdelyi, and the name went to the heart of his emerging grand plan. “What we were doing was almost like a concept. I realised that what you needed wasn’t musicianship, what you needed was ideas. Anything that worked, we kept. A lot of things were discarded, we were dropping things left and right – if it didn’t work, boom, it was out. We were very conscious about what felt right.”