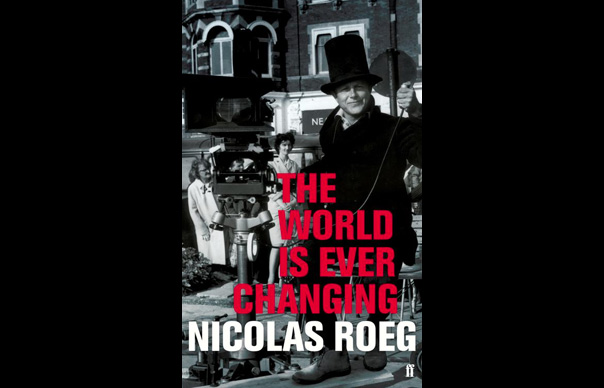

Nicolas Roeg is most widely known for the superlative run of films he made during the 1970s – including Performance, Don’t Look Now, The Man Who Fell To Earth and Bad Timing – but as his memoir, The World Is Ever Changing reveals, his interests are many and wide-ranging.

In fact, the tendrils of Roeg’s career stretch in both directions: back to his first job in 1950 through into the 21st century. His most recent film was 2007’s Puffball. Arguably, there are few directors who are better placed, then, to consider the tremendous sea changes that have occurred in British cinema over the last six decades. The World Is Ever Changing is part autobiography, but also a means for Roeg to pass down his accumulated knowledge and experience.

At this point, it’s worth mentioning that readers expecting fruity yarns about, say, David Bowie will be disappointed. The World Is Ever Changing – which takes its name from a line of dialogue in The Man Who Fell To Earth – comes without an index. This is not the kind of book where you can casually look up “Jagger, Mick” in the hope of finding some salacious gossip about his antics with Anita Pallenberg on the set of Performance: Roeg is a very much a gentleman of the old school, and the dishing of dirt is not on his agenda. But nor is it especially scholarly. In its tone, The World Is Ever Changing is conversational and leisurely – a bit like a wonderfully digressive fireside chat with a kindly uncle – with Roeg referencing a myriad of sources, from Abel Gance’s Napoleon to the poetry of Auden, Poe and Housman and the paintings of Bruegel and Velázquez, as he explains the thought processes and inspiration behind his own works. Meanwhile, very much in keeping with Roeg’s films, The World Is Ever Changing doesn’t have a chronologically structured narrative; instead, it’s divided into chapters according to themes – “Image”, “Sound”, “Script”, “Directing”, “Actors” and so on.

Roeg’s career began in the early 1950s, where his first job was at Marylebone Studios, making the tea and running errands, before progressing to a French dubbing studio run by Major De Lane Lea, a former British intelligence officer. Roeg’s early credits – as an assistant camera operator or focus puller – consist of long-forgotten films like Cosh Boy, Passport To Shame and the brilliantly titled Jazz Boat. There are some smart, funny tales about encounters with Clark Gable and Jacob Epstein, and Roeg is sharp on the awkward transition from black and white to colour filming. Early in the book, he recounts a story about a little boy and his mother who, while watching a location shoot in London, asked Roeg if they could look through the camera. When the mother took her turn, she said to Roeg, “Oh, it’s in colour is it?” Continues Roeg, “She was expecting the image to be in black and white. Se hadn’t associated the camera with seeing the world as she saw it with her own eyes. Black and white was what was most natural in films.”

Roeg’s big break came in 1962, when he was hired to work on Lawrence Of Arabia for David Lean. In Roeg’s book, Lean cuts a marvellous, if rather distant, figure, smoking “rather elegant, long cigarettes”, and who “didn’t take kindly to any sort of structural or production suggestions”. Roeg is witness as the film’s second unit cinematographer André de Toth is dismissed from the shoot for proposing an alternative way to shoot the Tafas massacre; Roeg took on his duties (Roeg was later fired from Doctor Zhivago after similarly making creative suggestions to Lean).

After Lawrence, Roeg worked as director of photography for Roger Corman, François Truffaut, Richard Lester and John Schlesinger, before Performance in 1970. There is very little here about Jagger – or indeed the film itself – thought Walkabout and particularly Don’t Look Now feature prominently in the book. Roeg keeps coming back to Don’t Look Now, one of his greatest films, gradually unpeeling its layers. In one of the most informative chapters – “Mirrors” – Roeg sets out to explore the use of mirrors in his own films, but manages to take in Orson Welles’ The Lady From Shanghai and The Rokeby Venus by Velázquez. Most of all, Roeg’s book feels like a collection of ideas – some of which he can tease into a thread, but at other times he ascribes to a kind of curious coincidence. He ponders on whether or not it’s important that the wife of sculptor Antony Gormley is the daughter of the couple whose farmhouse features in the early scenes in Don’t Look Now. “I don’t know why I connect these odd stories to magical thought,” he admits. But cumulatively, the impression here is of a restless and keen intellect, a man who – even in his 85th year – is willing to embrace new ideas. After all, why else would you call your autobiography The World Is Ever Changing? A chapter towards the end of the book, “Disjecta Membra”, manages to weave together a curious meeting with a medium, who arrives unannounced on Roeg’s doorstep looking for a “Reggie Nicholls”, some thoughts on reincarnation, neuroscience, and “the mysteries of the present day world.”

Roeg’s book ends with a coda set in Venice, during the shoot for Don’t Look Now. In the background of one shot, Roeg notices a poster for an old Charlie Chaplin movie – the title in Italian, Uno Contro Tutti. One Against All. “How true that turned out to be,” he writes.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner.