His soft voice, withdrawn nature and short life have given rise to a myth of NICK DRAKE as a tragic figure. In fact, this was a man with a robust musical identity, and a far-reaching plan for his songs. Forty years after his death, his producers JOE BOYD and JOHN WOOD, and contemporaries including RICHARD THOMPSON, ASHLEY HUTCHINGS, DAVE MATTACKS and BEVERLEY MARTYN remember a musician of uncompromising vision. “It was hard to figure out,” says Thompson. “He seemed to go to places people hadn’t gone to before.” Words: John Robinson.

Originally published in Uncut’s October 2014 issue (Take 209)

____________________________

Walk down Old Church Street, past the Manolo Blahnik outlet and the gardeners tending their employers’ hedges, and you’ll eventually arrive at a Georgian building set a little back from the pavement. Today, it’s been converted into desirable residences, tucked away near Chelsea’s King’s Road.

Between 1964 and 1976, however, this was the site of Sound Techniques studio, effectively the cradle of British folk rock. Here, Joe Boyd and engineer John Wood recorded mesmerising albums for Boyd’s Witchseason Productions: by Fairport Convention, The Incredible String Band, Sandy Denny, John Martyn and Nick Drake. The building began life as a dairy. A cow still looks down benignly from the exterior brickwork.

“It was a good space,” remembers Ashley Hutchings, then in Fairport Convention. “We recorded so many albums there, it became home. You popped in and out, and someone would be playing there. It was a nice place to be, Chelsea. The sun always seemed to be shining. We had all the time in the world.”

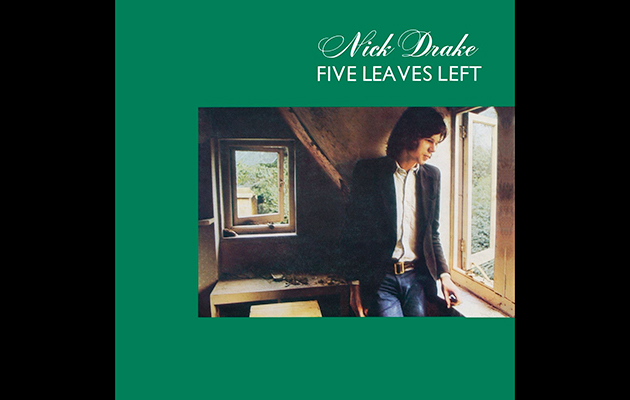

Forty years ago, in July 1974, Nick Drake visited Sound Techniques for the last time. The sun was certainly shining, but the material he now approached originated in worse weather. Drake’s work always seemed to have a seasonal logic. His 1969 debut, Five Leaves Left, was crisp, autumnal, and ordered as a school’s Michaelmas term. The looser Bryter Layter (1970) suggested an urban pastoral idyll, grass browning in a summer park. On 1972’s Pink Moon, the branches of Drake’s music were still starkly beautiful, but bare. Believing he had enough material to begin a new album, he now entered Sound Techniques again.

“Nick came to see me in the winter,” remembers Joe Boyd. “It was a dark, cold time. He was very distressed, and I was very distressed at how distressed he was. I said, ‘Well, let’s start recording again.’ Then I had to go back to California, and there was a gap. When I returned, we went back into the studio, in the summer.”

Over what Boyd remembers as two consecutive nights, he and John Wood worked with Drake on four songs, among them “Hanging On A Star” and “Black Eyed Dog”, a piece recounting a haunting by an unshakeable foe, delivered in an eerie falsetto reminiscent of Skip James’ “Devil Got My Woman”.

“With Pink Moon, some songs on that were very dark,” says Richard Thompson, the Fairport guitarist who guested on Five Leaves Left and Bryter Layter. “But this was a degree further off the edge.”

“John [Martyn] brought it back from Island, and said, ‘This is the latest from Nick…’” remembers Beverley Martyn, one of Drake’s closest friends. “Nobody had heard anything as real as that. It was him stripped bare.”

“The impetus to go in the studio had been because he was so unhappy and so disturbed,” says Joe Boyd. “I was viewing it first and foremost as therapy, because he always loved being in the studio. I didn’t hear the lyrics until he overdubbed them on the guitar parts.”

And when he did?

“It was terrifying. It was really alarming,” says Boyd. “But it was tremendous. It was quite extraordinary.”

It was a painful revelation. But, even in the grip of a fatal depression, Nick Drake was as in control of the direction of his music as he had been for the previous eight years. As distressing as it was for his friends to hear, he still knew precisely what it was that he had to do.