Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

CHAPTER TWO: THE TRUE ONE

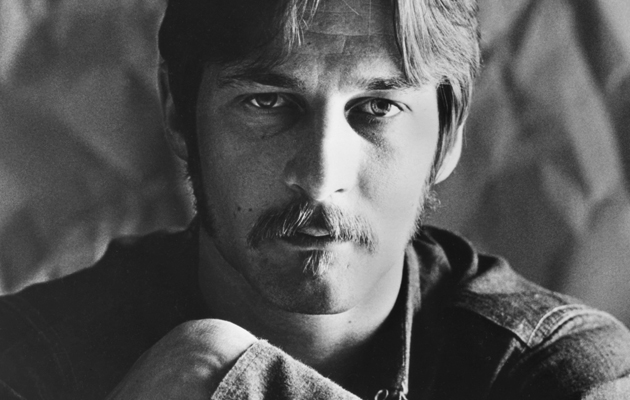

By the early ’70s, Clark had abandoned LA for the rustic confines of Mendocino in Northern California. Country living stabilised him, resulting in a visionary trilogy: 1971’s White Light, 1972’s Roadmaster, and 1974’s No Other.

“There was no panic, no pressure, it was kind of a golden era,” says Gary Mallaber, the Steve Miller Band drummer who played on White Light. “We listened, we arranged, we performed until we all felt that was the take.”

“I don’t know how to rightly explain this,” Clark later mused about his songwriting, “except that there was philosophy involved. Dylan in a way is a philosopher, he’s a deep thinker, John [Lennon] too. I consider Lennon and Dylan two of the best minds that we had, or have, in the 20th century… And they weren’t what you would call religious guys. They were spiritually connected. That vibration came across very strongly from The Beatles to us [The Byrds].”

Success, though, was not forthcoming. He only toured the White Light album and, with perfect Clark-ian irony, his most straightforward country/rock effort, Roadmaster, only made it to American record shops as a Dutch import. By 1974, though, on the back of an ill-fated Byrds reunion, he was somehow ready to unleash No Other. Producer Thomas Jefferson Kaye gave the album a Spectorian wall of sound, and the dense mix of keyboards, strings, percussion, chorale vocals, and layered guitars stands as Clark’s masterpiece.

“There were some boundaries being broken on every level,” observes Jackson. “Gene brought a seriousness to this thing that not even Gram brought. There was a nobility to Gene, one that I just kinda took to be a natural part of his personality.”

“The album was written when I had a house overlooking the Pacific Ocean in Northern California,” said Clark. “I would sit in the living room, which had a huge bay window, and stare at the ocean for hours. I would have a pen and paper, and a guitar or piano, and pretty soon a thought would come and I’d write it down or put it on tape. In most instances, after a day of meditation looking at a very natural force, I’d come up with something.”

Stephen Bruton, a Texan who’d recently backed Dylan, played guitar on No Other: “Gene was really talented. He was a kind of a loner guy. He had a cool voice, but it was also kind of a fragile voice, he was a fragile guy. I played with Gene several different times. It was always pretty wild. We were pretty crazy.”

In recent years, No Other has been routinely – and justifiably – acclaimed as a Smile for the ’70s, arguably the culmination of Gram Parsons’ Cosmic American Music. But at the time, the reception was less warm. Asylum’s David Geffen had been taken by Clark’s songs on The Byrds’ reunion album. But upset that his $100,000 budget for No Other had produced only eight measly songs, Geffen cut promotion, snuffing hopes for Clark’s commercial renaissance.

Unable to reproduce the lavish sound of No Other live, with no record label support, Clark was now forced back onto the road out of financial necessity. The 1975 Silverado tour (a live album from the tour is planned for summer 2008) saw the songs redefined by Appalachian triad harmonies and country arrangements. But conditions were spartan – the singer, his band and no roadies stuffed into the back of a Dodge van. And while Clark’s ego was battered by the ignominious conditions, he was still suffering from chronic stage fright. The only thing for him to do, it seemed, was to drink more and take more drugs.