https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O2MOuMWUa70

The twice-daily, hour-long commute to and from Amazon Studios along the M62, soon gave way to another journey and a different luxury hire car. After three weeks at Amazon, the band relocated to Ridge Farm, a residential recording studio near Horsham in Surrey. From there, the band’s driver Dave Harper, recalls they would travel to press engagements and meetings in a black limousine. “It didn’t appear to have a key for the ignition,” Harper notes. “It was all a bit dodgy. You put a large screwdriver, a big one, in the ignition and that’s how you started it. The boot didn’t have a thing to hold it up, so you had to use a broomstick. It was originally a funeral cortege car from Holland. Morrissey once asked me about the history of the vehicle. He was sitting behind me. He was in one of his chatty moods. I said, ‘It used to be a funeral cortege car from Holland.’ He said, ‘I wish you hadn’t told me that.’ He didn’t talk to me for the rest of the journey.”

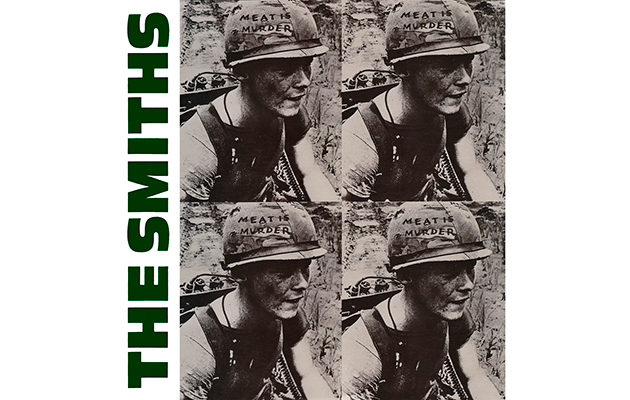

While based at Ridge Farm, the band finished work on Meat Is Murder. Key among that last batch of songs was the title track. “It was me, Mike and Johnny jamming out this very mellow, repetitive riff,” recalls Andy Rourke. “It just happened organically. Morrissey already had the lyrics.”

“There was no demo,” adds Stephen Street. “The chords are quite strange with that song and they wanted to create an atmosphere. So Johnny sketched out the chords, then we marked it out with a click track, put some piano down, and reversed the first notes to creative this oppressive kind of darkness. Morrissey handed me a BBC Sound Effects album and said, ‘I want you to try and create the sound of an abattoir.’ So there’s me with a BBC Sound Effects album of cows mooing happily in a field. It was a challenge, but I really enjoyed it. I found some machine noises and put them through a harmoniser and turned the pitch down so they sounded darker and deeper. I did the same things with the cows, to make it sound spooky. It was like a sound collage. The band learnt how to play it live after we’d recorded it.”

“The aspirant moment is the title track,” wrote Morrissey in Autobiography. “Each musical notation an image, the subject dropped into the pop arena for the first time, and I relish to the point of tears this chance to give voice to the millions of beings that are butchered every single day.”

Morrissey had become a vegetarian when he was “about 11 or 12 years old,” he told PETA, the animal rights organisation, in 1985. “My mother was a staunch vegetarian as long as I can remember. We were very poor and I thought that meat was a good source of nutrition. Then I learned the truth. I guess you could say I repent for those years now.”

The issues of vegetarianism and animal rights had been thrown into sharp relief a few years earlier with the release of a documentary, The Animals Film. “The matchstick which ignited animal rights in the mainstream in the UK was when Channel 4 aired The Animals Film in November, 1982,” explains Dan Mathews, PETA’s senior vice-president. “There were active groups for decades before, but this film brought the disturbing images to the masses. It connected to the broader political climate, especially to the UK’s class warfare, as animal issues like fur, fox hunting and foie gras were tied to the upper classes.”

“These were the issues around,” adds Billy Bragg. “If you went out of demos, there were always animal rights activists knocking around, no matter what the demo was. It was part and parcel of what the Left addressed at the time.”

Accordingly, if Morrissey was a practicing vegetarian it followed that his fellow bandmates adopt a similar dietary regime. “You can’t record an album called Meat Is Murder and slip out for a burger,” observes Andy Rourke. “After we used Ridge Farm, all our other recordings were done in residential studios. It was great. You could fit your own schedule. We used to work, then have lunch, sandwiches, maybe 2pm, then at 6 or 7, it would be dinnertime. You had your own chef there, who’d cook amazing food. We were always thinking with our stomachs.”

While at Ridge Farm, Stephen Street remembers the menu was “meat-free and fish-free. It was a fait accompli. I knew Andy and Mike would give in every now and then. But certainly, when we were together in the studio, no-one ate any meat. Their diet was bloody awful. It was chocolate and crisps. I remember thinking that Johnny looked so slight. No wonder, he hardly ate anything.”

“One time, we stopped at a service station to get some breakfast,” says Andy Rourke. “Everyone ordered scrambled eggs or fried eggs or whatever. I ordered the full English breakfast. When it arrived, Morrissey left the table. Then Johnny left the table. Then Mike left the table. So I was sat on my own with this English breakfast feeling very uncomfortable. I went vegetarian after that.”

“On one of our many trips, we stopped at a service station with a Little Chef,” adds Dave Harper, like Rourke another fan of the traditional fry-up. “In those days, if you ordered an all-day breakfast it came on a plate decorated with a farmyard scene. So you had the joy of eating bacon and sausages off a plate with pictures of pigs on it. I thought it was quite funny, particularly eating it in front of Morrissey. He didn’t make a scene, he just said, ‘Why have you done that?’ I replied, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about. Done what?’ He didn’t harangue me, or never forgive me for eating meat. It wasn’t the right environment for him to start sounding off about politics. It never came up. But it was a big thing: what does Morrissey eat? Biscuits, cake, ice cream…”